Swiss corona protests: conspiracy theories vs political rights

Switzerland is now well into phase two of its three-stage loosening of Covid-19 restrictions, but this hasn’t stopped citizens gathering to protest against the government’s measures.

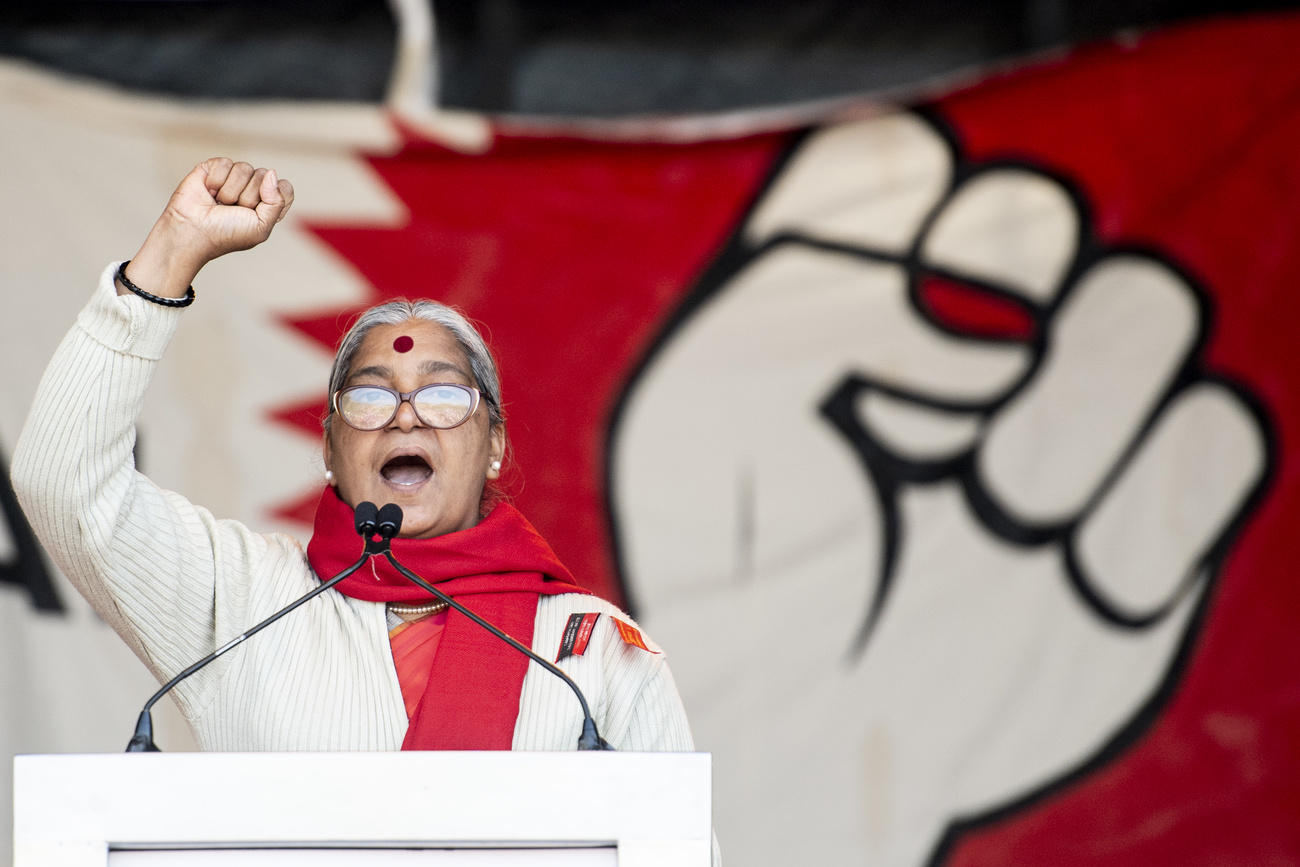

For three weekends running, they have defied a ban on political demonstrations – as well as a general ban on meetings of more than five people – and have gathered in small but loud numbers to protest the restrictions on freedom.

What do they stand for?

On one hand, the activists are concerned about the suspension of political rights and the extraordinary powers taken up by government to combat the virus.

“This is not a demonstration, it’s a vigil,” one of the Bern organisers, Alex Gagneux, told swissinfo.ch last week. For him, such a “vigil” is necessary in front of parliament because “the constitution has been suspended” by the government’s “disproportionate” actions.

Posters at the events carried slogans like “RIP democracy, 1291-2020” (referring to the year Switzerland was apparently born) and “#StayAwake for freedom and self-determination”. It’s about freedom in the large sense of the word, and a fear that political liberties taken away by Covid-19 aren’t being handed back quickly enough.

Freedoms or fictions

However, freedom is a big word, and beyond the right to protest – a right which authorities this week clarified is not suspended for demonstrations with fewer than five people – the protests have also drawn in a range of less fundamental issues.

Other placards seen over the past few weekends included:

“Give [Bill] Gates no chance”

“No to forced vaccinations!”

“Stop Corona Hysteria!”

In other parts of Europe, Covid-19 has led to events like the burningExternal link of 5G masts, seen as being linked to the virus. In Switzerland too, the protests have attracted various disgruntled voices and has led to the term “conspiracy theory” popping up in the media (it has also inspired detailed fact-checking effortsExternal link).

Why the flowering of such ideas?

In a 2018 book, “Total bullshit: getting to the heart of post-truth”, Fribourg neuroscientist Sebastian DieguezExternal link writes how the idea of “bullshit” – defined as a disregard for the idea of truth, rather than a lie as such – is at the centre of a lot of contemporary problems, including conspiracy theories.

Such ideas easily spread in an environment of fake information and scepticism, he tells swissinfo.ch. They are often “deliberately vague”, which also makes them very difficult to disprove. “They are subject to the law of asymmetry of bullshit: it’s a lot more difficult to disprove than to come up with them in the first place.”

And often, he adds, as well as being top-down stories invented for political purposes, such theories can also spring from the bottom-up, driven by people who go beyond a healthy scepticism to a simple unwillingness to believe any facts they are told.

“Some people just read what confirms what they want to believe,” he says. On an individual level, he says, “you have to ask them to explain what they are trying to say, and get them to back it up with an argument. On a larger scale, there is fact-checking, there are laws, fake news algorithms, but it’s very difficult to counter.”

Political headache

Likewise, drawing the line between legitimate political protest, conspiracy-led disruption, and public health concerns is difficult. Do people have the right to protest for whatever belief they choose to hold?

Dieguez is not for banning demonstrations – which, incidentally, are increasing in number, in Switzerland. But he does say such conspiracy theories, especially when they are used opportunistically in times of crisis, are for him dangerous. The demonstrators “are part of a trend of social disruption that is deeply anti-science, anti-“elite”, and populist,” he says. Nothing the government says or does can change their minds – “they will be ‘against’ it in any case”.

In its editorialExternal link last week on the protests, the Berner Zeitung took a more conciliatory line: for it, the government “did not clearly enough explain its reaching into freedom and economic liberties”. Its headline: “Not all dissenters are crackpots”.

Daniel Koch, the government’s top health official on the crisis, and its top communicator when it comes to the emergency measures, was also forced to wade into the waters on Monday when he was asked about the demonstrations and the danger for public health. He said the question was a political one.

With the government expected to discuss the issue by month’s end, according to the Le Temps newspaper, the answer will also be political. In the meantime, more protests are planned for this weekend.

More

Coronavirus: the situation in Switzerland

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.