Watch this space for Titan mission

Swiss technology is set to play a key role when one of the most exciting space adventures ever enters a crucial phase on Christmas Day.

After a seven-year journey from Earth, the Huygens probe of the European Space Agency is preparing to land on Titan, the largest and most mysterious moon of Saturn.

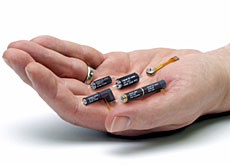

Systems from Contraves Space in Zurich will help separate the probe from its mother ship, Cassini, which was built by NASA in the United States.

“We provided three main elements – the separation mechanisms that are going to separate the Huygens probe from Cassini. We also delivered the front shield and the back cover,” Contraves Space CEO Umberto Somaini told swissinfo.

On Christmas Day, Huygens will slowly separate from the orbiter Cassini. Spinning seven times a minute and after a voyage of more than three billion kilometres, the small, saucer-shaped spacecraft will speed like an arrow toward the smog-covered moon.

Unique environment

It is due to dive into Titan’s atmosphere on January 14, hopefully to provide details of the unique environment of Titan, whose chemistry is assumed to be similar to that of early Earth just before life began, 3.8 billion years ago.

The probe will slam into Titan’s upper atmosphere at a speed of around six kilometres a second or ten times faster than the Concorde airliner.

ESA says that the spacecraft’s heat shield will reach a temperature of 8,000 degrees Celsius and its outer skin will glow orange-red during the most intense part of the descent.

“The front shield is particularly important because it has to protect the probe when it enters Titan’s atmosphere. There will be enormous temperature and aerodynamic friction. Without the shield the probe would just burn up,” Somaini explained.

Afterwards, with the probe’s speed having dropped to 1,400 kms per hour, the charred shield will fall away, enabling parachutes to open.

If all goes well, cameras and other instruments on board Huygens will then sample the air and take pictures of the alien landscape below. The data received will be sent over a few hours to Earth via Cassini.

Solid ground?

Two hours later, Europe’s explorer is due to land on Titan but no one knows whether Huygens will touch down on solid ground or splash down into an alien sea.

Scientists are hoping in particular that the probe will tell them if the clouds around Titan are hiding oceans or lakes of methane or ethane.

They also want to look in the clouds for evidence of volcanoes and precipitation.

The international Huygens-Cassini mission is the most ambitious space adventure to date, costing a total of $3.3 billion (SFr3.81 billion).

Huygens, which weighs in at 350 kgs, cost SFr400 million alone. The Swiss contribution to the mission was SFr26 million.

Somaini says that both staff at Contraves Space and some of its pensioners who worked on the project will be looking keenly to see how the mission develops.

“We are pretty excited because it is a delicate mission… and we don’t what it is like exactly on Titan. If it is successful, it will be an enormous relief but there will also be a lot of pride for everyone involved in the mission,” he said.

“There is no substitute for success and being part of a success is a great motivator. We’re also a bit nervous because there is always an element of risk,” he added.

swissinfo with agencies

Cassini-Huygens was launched from Florida in October 1997.

It took almost seven years to reach Saturn, travelling nearly 3.5 billion kilometres.

The 5.6-ton spacecraft is made up of two parts – the Cassini orbiter and the Huygens probe.

Three other Swiss companies and Bern University also contributed to the mission.

Cassini-Huygens is the first spacecraft to orbit Saturn.

Since arrival at Saturn on July 1, Cassini has been sending back new information about Saturn, its rings, moons and magnetic field.

Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens discovered Titan in 1655.

Italian-French astronomer Giovanni Cassini discovered Saturn actually had two main rings around it. The gap between them is still called the “Cassini Division”.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.