The Swiss hunt: collecting the reward for a year’s work

The strictly controlled hunting season is underway in Switzerland. Clare O’Dea is initiated into a ritual that draws tens of thousands of Swiss to the mountains with their rifles each autumn.

We are scrambling over loose rocks on the steep mountainside when a shot rings out. It is a quarter to eight on a pristine, sunny morning on the Euschels Pass, in the western part of the pre-Alps. Around us, the peaks create a natural amphitheatre for this most ancient of human dramas – the hunt.

There is no time to stop. We are out in the open and must make it to the hiding place before the chamois arrive. I step with extra care, mindful of the story I heard the night before about the hunter who broke his leg when he slipped between two rocks. Hunting lore is full of cautionary tales.

A short time later we reach a boulder the size of a minivan which will be our base and vantage point for the rest of the morning. My hunting guide is called Thomas. Fellow members of his hunting club, Diana Sense Oberland, are spread out around the pass in pairs.

The hunters have the starring role today; the unfortunate chamois is the victim. Native to European mountains ranges, these brown and grey goat antelopes are hardy climbers who startle easily. For most of the year they are safe from human harm but this is day three of the two-week chamois hunting season when 15% of the population will be culled. Next in line are red deer and roe deer in the lowlands.

Thomas sets up his spotting scope and finds his colleagues on the far side of the valley where the shot came from.

“They got one,” Thomas whispers. “Take a look.” I cover one eye and look through the viewfinder at the scene more than a kilometre and a half away high up on the shady side of the valley.

The chamois has to be gralloched and cleaned out straight after killing. The view is grainy but I realise that is what I am looking at. The regulations state that the animal’s innards must be buried or covered with stones. Then, as soon as possible, it must be carried to place where it can be hung until inspected by the local wildlife ranger.

Magnificent backdrop

We’ve been on the move for two hours and it’s time for breakfast. Thomas shares his provisions – dried venison sausage and brown bread. The boulder provides excellent cover and we keep an eye on the green slopes between the scree and the fir trees where a small group of chamois was spotted the day before.

To the southwest lies the regional nature park of Gruyère-Pays d’Enhaut, home to French-speaking farmers and their famous cheese. To the northeast is Gantrisch Nature Park, a mountainous area adjacent to the Bernese Alps whose few scattered residents are German-speaking.

The mountains above the Euschels Pass, a geographical link between the country’s two main language regions, are owned by a farmers’ cooperative whose cows, sheep and goats are brought to graze there in the summer months. The proprietors of a handful of mountain huts look after the livestock and provide hospitality to anyone passing through.

Hunting is a waiting game. The jingle-jangle of cow bells travels up from the valley below, interspersed with lowing and the distinctive whistle-like squeak of the alpine marmots. An eagle circles in the clear blue sky overhead.

“This is where we shoot,” Thomas taps the side of his chest under his arm. “One clean shot in the heart and lungs. If we do our job right, they drop dead on the spot.” The golden rule is never to chase chamois. They will outrun you.

“What attracts me most to hunting is the connection with nature. It’s also, not least, a way to get organic meat. The animal is born and grows up in the wild and is killed with one clean shot. Where else would you get such meat?” Thomas

Luck of the draw

Not all of Fribourg’s 760 licensed hunters can go out and shoot a chamois this year, only those who applied and were allotted an animal in the annual cantonal hunting draw. Thomas was lucky, he has a permit to shoot one chamois this season, a female without young. The challenge is that he has to take the shot from no more than 200 metres. It is going to be a long day.

We wait for several more hours but the chamois do not come to this particular pasture. The day has become too hot, and the animals will seek shade. So we trek back down to the nearest mountain hut of Obere Euschels to regroup and find out what the others have to report. For these hunters, camaraderie is at the heart of the experience.

There has been one kill today and celebrations are in order. Twenty-seven-year-old Simon, the successful hunter, is the youngest of the group. The hunters share snuff and drink a round of schnapps together, holding the glass in the left hand for luck and invoking the hunters’ toast and parting phrase, ‘Weidmannsheil’ (good hunting).

Between toasts of schnapps and rounds of snuff, Simon slips away from the table to show me his chamois.

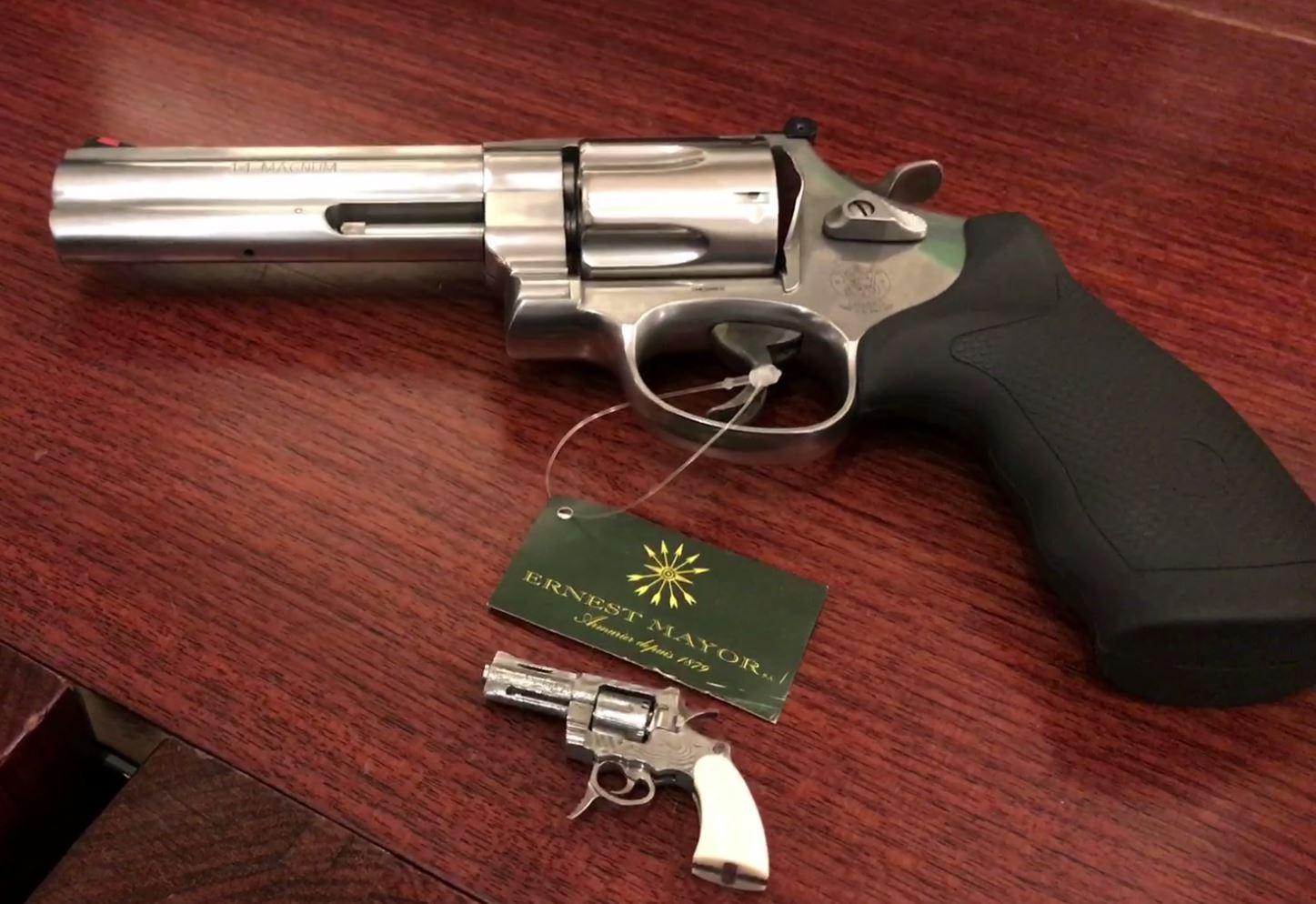

She is hanging from a beam in the stable with a branch of greenery between her teeth. “Her last meal,” Simon says. “We do this out of respect.” He killed the chamois with a single-shot .270 (Winchester) caliber rifle, a lightweight firearm popular with hunters in this part of Europe.

The animal has a distinctive black patch on her haunch and Simon has been observing her since May. “I watched her for twelve hours on Saturday but I couldn’t get closer than 300 metres. Then the mist came. Today, I knew exactly where to wait. When I shot her it was an emotional moment but I felt proud.”

Harvest time

Simon will sell the carcass whole to a restaurant for CHF200 ($200), less than the cost of the chamois permit. The basic licence in Fribourg is CHF200. Hunters then apply for a permit for each animal they want to shoot and pay the designated price tag – 250 for an adult chamois, 160 for an adult roe deer and 200 for a red deer. The price is tripled for hunters from outside the canton.

The men, who have taken time off work for this expedition, sit outside at a long wooden table, served by the elderly landlord who eventually sits down with his accordion and plays. Among the group, a carpenter, a retired print technician, a truck driver, a caretaker and a bank employee, but no one speaks about work here. We eat sausage, goats’ cheese and bread while passing hikers call out friendly greetings in French and Swiss German.

“This is our harvest after a year’s work,” the oldest hunter, Hugo, tells me. There are duties throughout the year for the members of the hunting club. Hugo helped save fawns from combine harvesters in the mowing season, he spent time doing forest maintenance work and he did his compulsory annual target shooting test.

“I grew up with hunting. My father was a hunter and his father before him. For me, it’s mostly about being close to nature,” Hugo adds.

“Hunting means a lot to me, it takes up a large part of my free time. The motivation can’t really be explained, it lies in our genes and in evolution. Hunting is a true passion.” Thomas

Evening watch

By late afternoon, it is time to get into position for the second attempt of the day. The hunters disperse and I follow Thomas again, this time heading for the other side of the valley. After another steep climb through the trees we have a new base that gives a perfect view of the open mountainside.

Soon there is some chamois activity. Above us, to the right, one who might be close enough to shoot but he is too high up on an inaccessible rocky face. The hunter has to be able to retrieve the body.

On the far side of the slope a pair of chamois appear and begin grazing. Though they are out of range, the male is nervous, and regularly retreats to the cover of the trees. Sometimes, through the binoculars, it feels as if he is looking straight at us, wary and distrustful. The female wanders around, relaxed.

The male’s caution pays off. The pair are destined to spend one more day together. They keep their distance for the evening, and it is impossible to get close enough to shoot without being seen. Thomas will shoot his chamois 24 hours later in the same pasture from a better position.

The sun has set and the light is rapidly fading when we pack up and begin the trek back to the hut where the men will spend the night. The curtain goes down on the hunt but it will rise again in the morning for more tension, tragedy and spectacle. Weidmannsheil!

Sixteen Swiss cantons operate a licence system for hunting, limiting the main hunting periods for the “high hunt” of chamois and deer to several weeks in the autumn. Nine cantons operate a territorial hunting system where communes grant hunting rights to hunting groups. Geneva is the only canton where hobby hunting is banned and the cull is carried out by wildlife rangers.

Based on 2016 figures, the most popular animals hunted in autumn are roe deer (43,616), red deer (11,873) and chamois (11,170).

The Swiss Hunting Association estimates there are 30,000 active hunters in Switzerland, including 1,500 women.

Hunting is widely accepted in Switzerland as an effective way to keep wild animal populations at sustainable levels. A September 2018 initiative to ban hobby hunting in canton Zurich was rejected by 84% of voters.

The demand for game outstrips supply in Swiss restaurants and supermarkets, with more than two-thirds of game imported.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.