The devil and Roger Federer

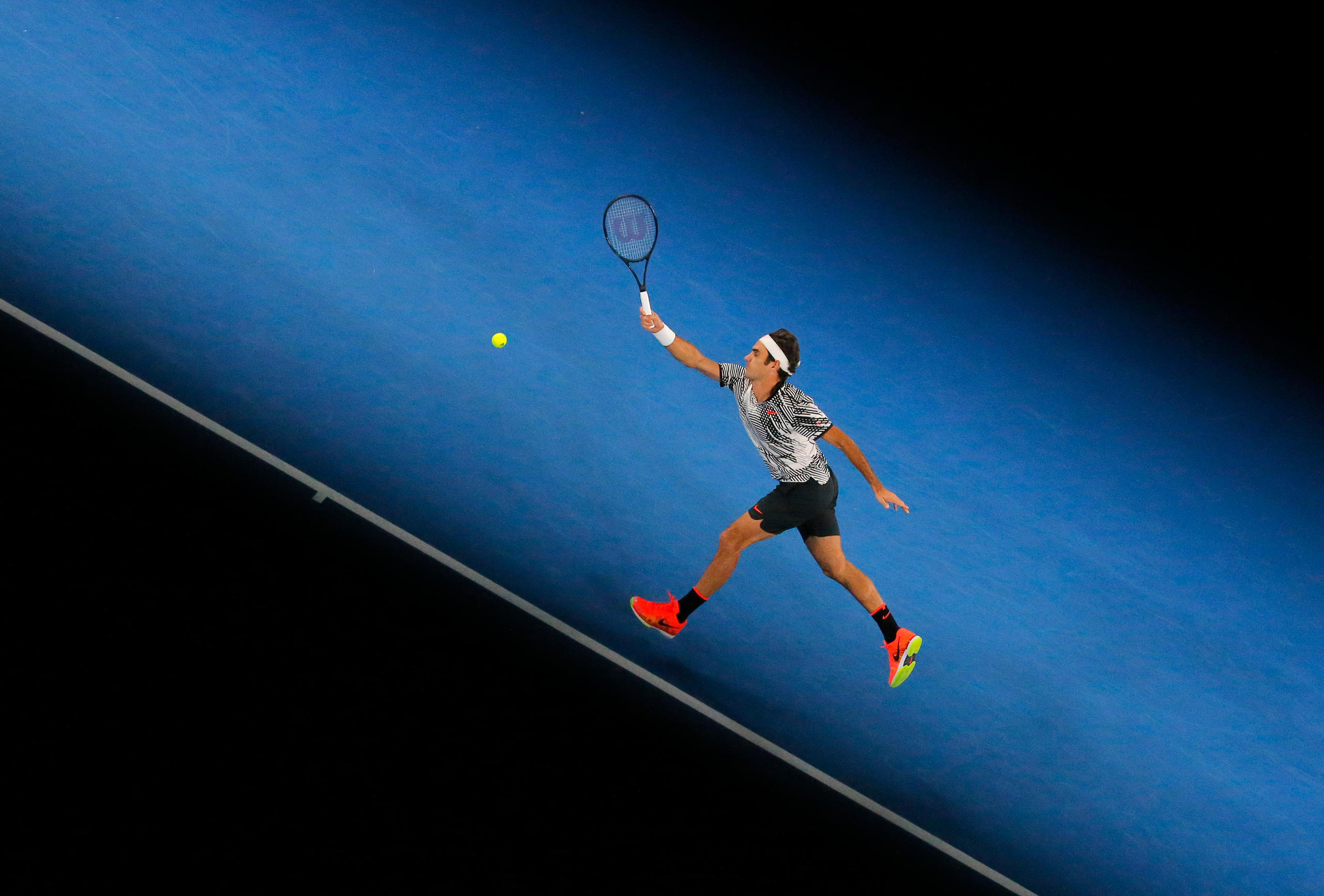

I know a grown man with not one but two framed images of Roger Federer in his house, the larger of which shows the sweatless Swiss revving up for a cross-court forehand that makes you all but duck in the hallway.

Another Federista is so loyal that, if I wobble home at 5am to find his hero shredding some poor chump in the televised Shanghai Masters, I know my friend is awake in his flat and available to text.

A decade has passed since David Foster Wallace took a break from fiction to describe the “mystery and metaphysics” of Federer’s tennis. Another writer, William Skidelsky, devoted a book to the same obsession.

More

Financial Times

External linkLionel Messi has achieved equal greatness in a much bigger sport. Usain Bolt is more charismatic. So if Federer has a special hold over middle-class men, something beyond his talent and stardom must do it for them: a sense that he is somehow good at life.

Urbane, uxorious, multilingual, emotionally expressive, faintly androgynous, Federer offered a different model of maleness to a generation reared after the eclipse of heavy industry and its associated virtues. He became, like Mary Tyler Moore during the rise of working women and birth control, a reference point for changing sensibilities.

The mistake is to sanctify him. Federer is credited with impeccable personal class, as if this matters tremendously. Tennis, like rugby, can be insufferable in its chivalric pretensions. When he beat Rafael Nadal for his 18th grand slam last weekend, pundits were as rapt by the magnanimity of these rivals as by their play. The mawkishness got in the way of the truth: that Federer is spikier than his reputation allows, and it makes him more, not less, of a model to emulate.

More

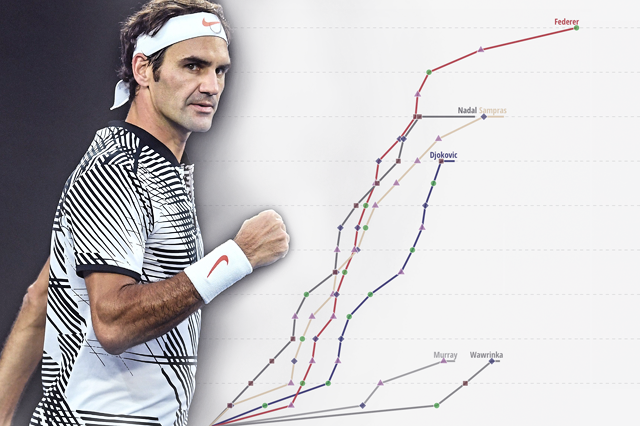

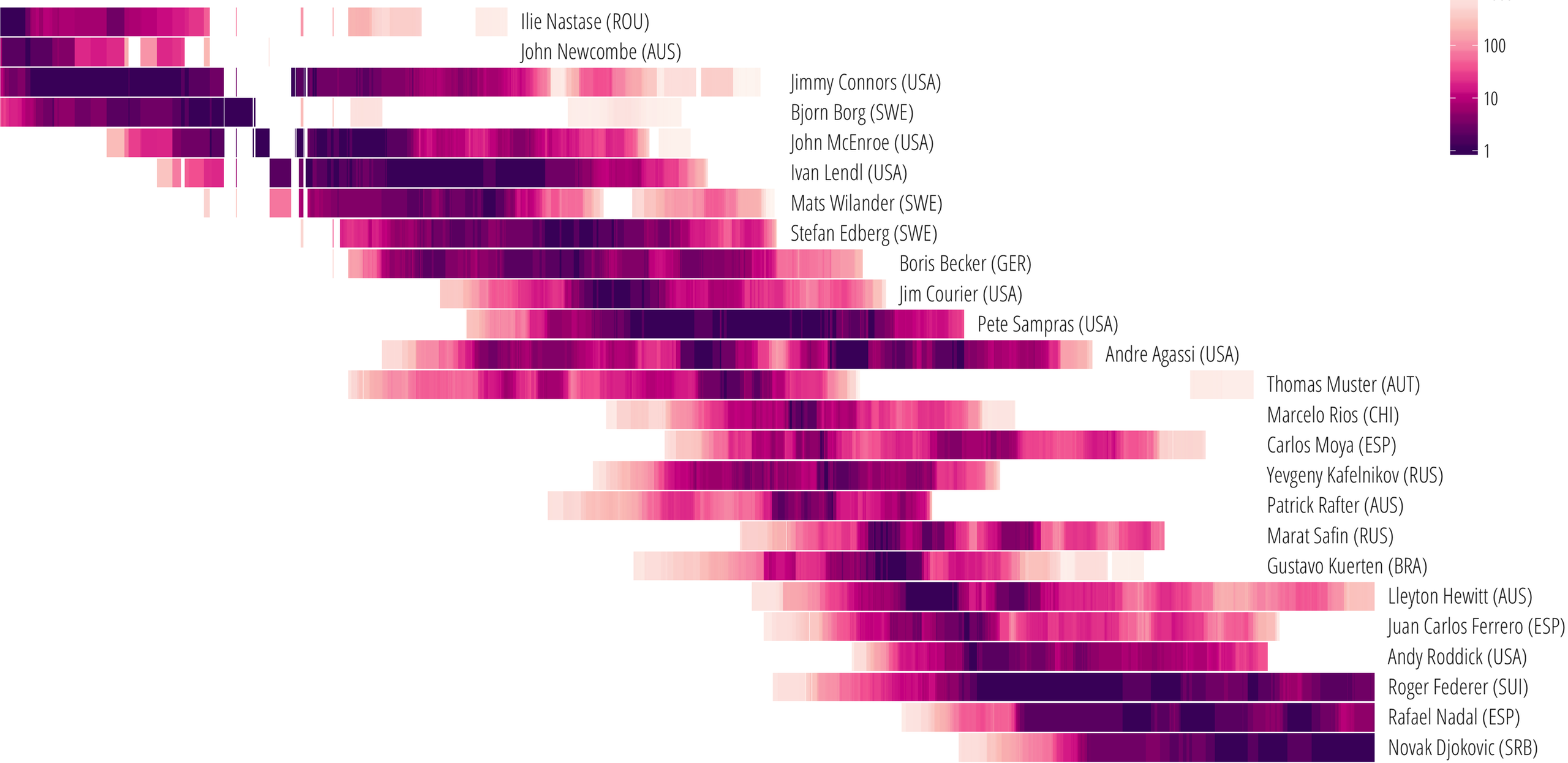

Federer’s path to 19 Grand Slam tennis titles

Go over the evidence. The young Federer bloomed a season or two late due, in part, to a volcanic McEnroe-grade temperament. He grew out of it but retained a flair for a barb (“To lose against someone like that,” he once huffed about Novak Djokovic, “it’s very disappointing”) and a boast. His bodily grace can look, to some eyes, like hauteur. A man who spent his best years in a monogrammed cream-and-gold blazer has no issues of self-worth. Even his 18th title came with criticism of the prolonged (some say strategic) medical break he took after losing a set.

This is not the rap sheet of a chainsaw murderer but nor is Federer a monk. He would be no use as a role model if he were. To prosper in life, or just to withstand its vicissitudes, a person has to possess some dark traits in controlled doses: aggression, swagger, ruthlessness verging on chicanery, an ability to block out other people and their judgments. Much more than a trace of this stuff and you are on to the first rungs of sociopathy. Much less and the world sniffs a soft touch. There is such a thing as the optimal amount of devil in a person, and it is not zero. Call it the Federer Quotient.

Everyone knows what zero looks like: the academic wizard who amounted to little in the world of work, the overnice friend who plays the doormat in a marriage, the old schoolmate who should have outdone you in life but lacked the vanity to even think in such terms. We flatter their goodness almost by way of consolation.

The problem is not that we overrate Federer’s niceness – although we do – but that we overrate niceness itself. To put so much store in outward manners suggests a superficiality on our part, not moral depth. To instruct children in decency above all else, when life will demand rather more than that, is to underprepare them.

Attempts to draw human lessons from sport tend to exaggerate the real-world application of teamwork, grace in defeat and other Corinthian pleasantries. More transferable are mental toughness, the projection of confidence even when it is insincere and the extraction of marginal gains through cunning.

“Nice guy” and “role model” have become synonyms in sport but a role model is someone who shows you how to move through the world as it is.

The confusion of the two concepts has given us the fashionable disdain for Cristiano Ronaldo, who overcame childhood hardship, parental bereavement and the culture shock of northern England to become Messi’s only peer at the summit of football. He goes at life in a way everyone should admire but something in the strut and the gamesmanship has made him the opposite of a role model in some eyes – a kind of anti-Federer.

In truth, they are similar. Federer has a controlled dose of the dark stuff. To get the most out of him as a template for living, do not look the other way.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2017

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.