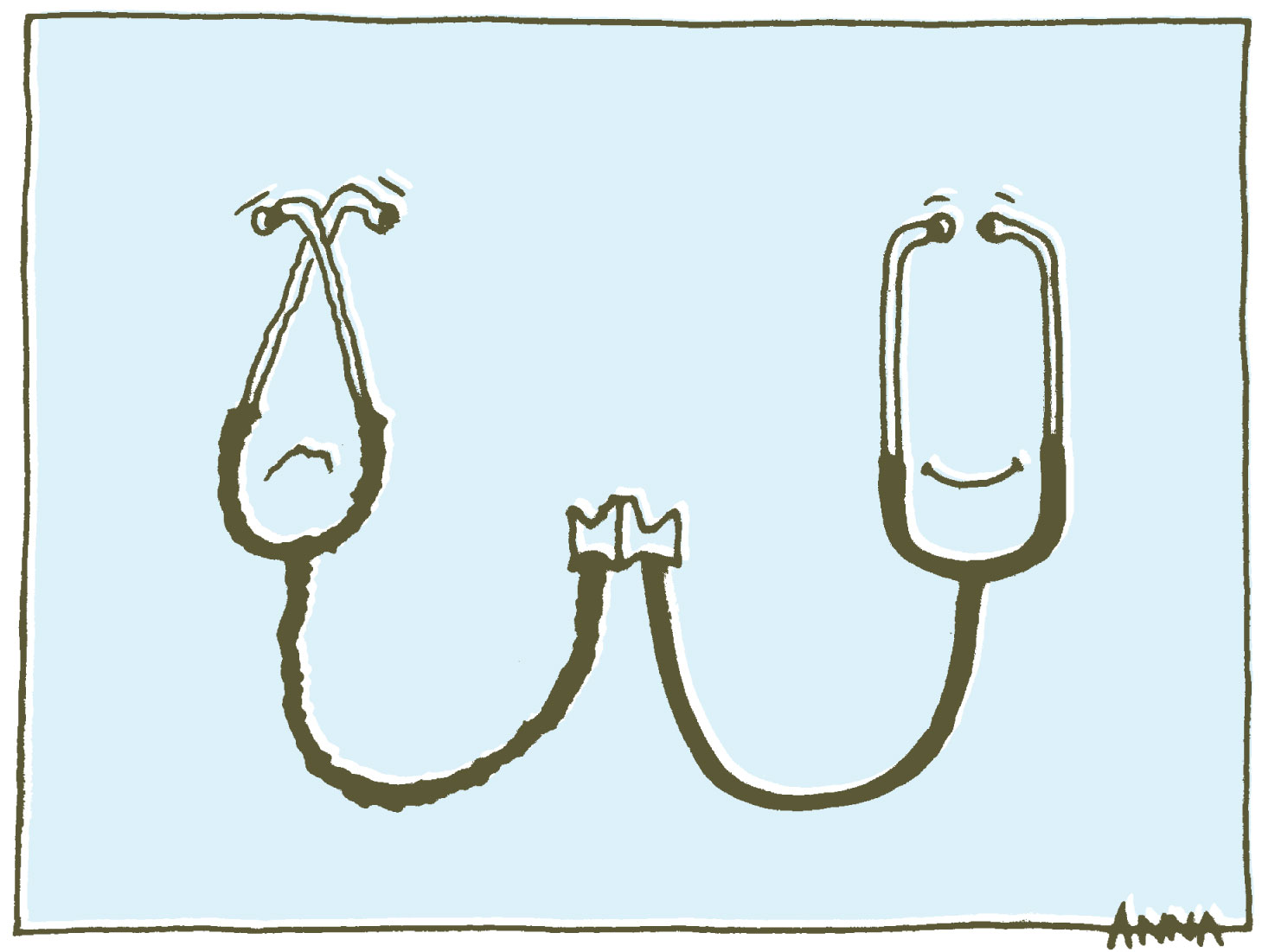

Switzerland faces a lack of new GPs

Fewer and fewer young doctors in Switzerland are choosing to become general practitioners, a trend family doctors protested against in the Swiss capital on Thursday.

If it continues, the decline in the number of GPs could have a serious effect on health care, they warn.

To better inform the general public of the situation, their association has launched a campaign demanding a change to health policy that encourages more students to embrace the profession.

Only ten per cent of medicine students plan on careers as family doctors. Meanwhile, half of Switzerland’s GPs are expected to retire in 2016, and by 2021, it is expected that 75 per cent will have retired.

Dr Bruno Kissling, who has a practice in Bern’s Elfenau neighbourhood, is one of those family doctors. He plans to work as long as he can, but retirement is on the cards for him too.

“I’m 62… and I still really like to work. I can’t imagine retiring at 65, but I do plan to withdraw from professional life at 68. I think that at some point you run out of the energy, but not the desire, to work,” Kissling told swissinfo.ch.

Strategy

In an effort to cope with the lack of new blood, the Swiss association of family practitioners has launched its campaign to raise support for the initiative “Yes to GP medicine”.

Kissling is also concerned about the pending shortage of doctors like himself. Although he doesn’t have a successor lined up, he does have a strategy. The idea is to merge his practice with those of interested colleagues.

“So we could expand our capacity while taking on young doctors, including those who want to work part time.”

His strategy is still not fully developed. “There are obstacles, because at my age you should not invest in a business that you cannot maintain for long.”

Nevertheless, he believes that the older family doctors should get involved because it is difficult for new doctors to establish a group practice from scratch.

A people person

Kissling, who was a child when he decided that he wanted to be a GP, says that he especially treasures the long-term relationships that a family doctor tends to have with his patients. In contrast, specialists see their patients in the short term.

“Accompanying people for ten or 20 years of their lives is something that occurs only in primary care medicine,” according to Kissling.

He appreciates communicating with the patients and seeking solutions – not just applying medicines and making a diagnosis, but rather considering the person’s illness and what they feel.

For Kissling, being a GP is both challenging and tough. This generally translates for him into 12-hour days, though that is something he says he can handle without any difficulty.

While many people spend their lunchtime consulting a menu, he is normally looking through his papers, looking after his administrative work. The most time-consuming part of this is responding to queries from insurance companies that want to know why he prescribed a certain medication or physiotherapy sessions.

He also has to sign off for the hours carried out by home nursing services for his patients, even though he admits he has no idea how to really estimate how much at-home care is needed for his patients.

His work also requires him to sign documents from retirement homes and certificates even though he has no influence on the decision process.

Death and costs

After dealing with his administrative duties, Kissling then starts making house calls, mostly at local retirement homes.

“I could hand over that work to another doctor,” he admits, “but a long-term relationship implies working with patients until the end of their lives.”

Death is a regular occurrence in this line of work.

“Usually we find a way so that people pass away peacefully. If the patient is not suffering and is prepared to go, it’s not something that I find hard to handle,” says Kissling.

“It is challenging, but also rather lovely to accompany people in this situation.”

Kissling does not believe that GPs are responsible for rising health costs, pointing the finger of blame squarely at the country’s hospitals.

“Our society does not want to consider how far we want to go with medical care,” he says.

“We can always find some other treatment and if you take it far enough you end up with clinical trials, where proven remedies are no longer the norm and where research begins. It is an expensive option and is that what we want?”

Switzerland spends the third largest percentage of its economic output on health care of 34 industrialised countries.

According to the Federal Statistics Office, healthcare expenditure in 2008 soared to SFr58.5 billion ($63.47 billion), or 10.7 per cent of gross domestic product. That is 5.9 per cent more than the previous five years.

It puts Switzerland among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s biggest spenders, with only the United States and France spending higher percentages of their GDP on health care at 16 per cent and 11.2 per cent respectively.

Each resident in Switzerland spent on average SFr7,589 on health care in 2008, or about SFr632 a month.

About two-thirds of the costs were covered by individuals and the basic health insurance that every Swiss resident must have by law. State contributions climbed from 16.2 per cent to 18.3 per cent.

In 2010, there were 30,273 doctors working in Switzerland (10,843 women and 19,430 men).

Nearly two thirds of the country’s self-employed doctors (13,550) work alone.

The average age of these doctors is 53, but is slightly lower for women (50).

Around 74 per cent of Switzerland’ independent doctors are also available for emergencies, while two thirds of them make house calls.

(Adapted from German by Susan Vogel-Misicka)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.