Shrinking glaciers to make room for power generation

The retreat of the alpine glaciers will not lessen the production of hydro-electric power in Switzerland. In fact, it will provide opportunities for building new dams and reservoirs in mountain terrain, increasing the capacity for power storage in the Alps, researchers believe.

Here is an idea that would appall environmentalists: using heat generated by atomic power to melt glaciers and use the resulting water to produce electricity. Proposing this was Zurich engineer Adolf Weber, who suggested building just such a hydro-electric power station in the Jungfrau region in the heart of the Swiss Alps.

An absurd idea? Of course. But this did not stop the Swiss government from referring the project for study to the relevant departments and institutions. In fact, the discussion took place in 1945. Fascinated by the amount of power released by atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, physicists and engineers were keen to find peaceful uses for nuclear power, as historian Guido Koller recalls. At the end of the consultation process, the proposal to use nuclear power to harness hydro power was deemed “impractical”, writes Koller.

4% of electricity from glaciers

More than 70 years later, Switzerland has five nuclear power stations, all of them located in valleys, and water is the most considerable renewable source for producing electricity. Almost 60% of our supply comes from hydro power, the highest percentage in Europe apart from Norway.

Swiss hydro-electric power stations mainly get their water from rainfall and snowmelt. For decades now, the melting of the glaciers caused by global warming has also been providing water for electricity generation, notes Bettina SchaefliExternal link, professor of hydrology at Bern University. She estimatesExternal link this share of power production at about 1.4 terawatt hours a year, which is 4% of the nation’s hydro-electric production.

+ find out why glaciers are melting

Melting glaciers fill alpine reservoirs in the winter when there is not enough snowfall, explains Stuart Lane, professor of geomorphology at Lausanne University. “By 2040, the glaciers will have melted so much they will no longer be able to provide this,” believes Lane, who finds the prospect worrisome.

However, the Axpo power group, which is the main producer of hydro-electric power in Switzerland, does not seem to be worried. “There may be somewhat less water for power generation after 2050. This reduction in the amount of water flowing into reservoirs may be offset by a change in precipitation – heavy rainfall – due to climate change,” Axpo spokesman Ueli Walther told swissinfo.ch by e-mail.

The disappearance of 1,500 Alpine glaciers “will not jeopardise national electrical production”, maintains Schaefli. On the contrary, it will create new opportunities for operators of hydro-electric facilities and development of renewable energy sources in general – in Switzerland and around Europe.

Europe’s “power pack”

In the Swiss Alps there are 200 pumped-storage hydro-electricity stations. Many are at an altitude between 1,000 and 2,000 metres. Man-made lakes are filled with water, which is then be released for electricity generation during shortfalls from other sources. When there is an over-production of power, water is pumped and stored back upstream.

This cyclical system works well at regulating electricity generation in Switzerland, and seems the ideal solution to make up for fluctuations in renewable sources (sun and wind). According to the Swiss government, pumped-storage facilities in the Alps – Switzerland’s biggest is in Canton Glarus – could act as a “power pack” for Europe.

More dams in the Alps?

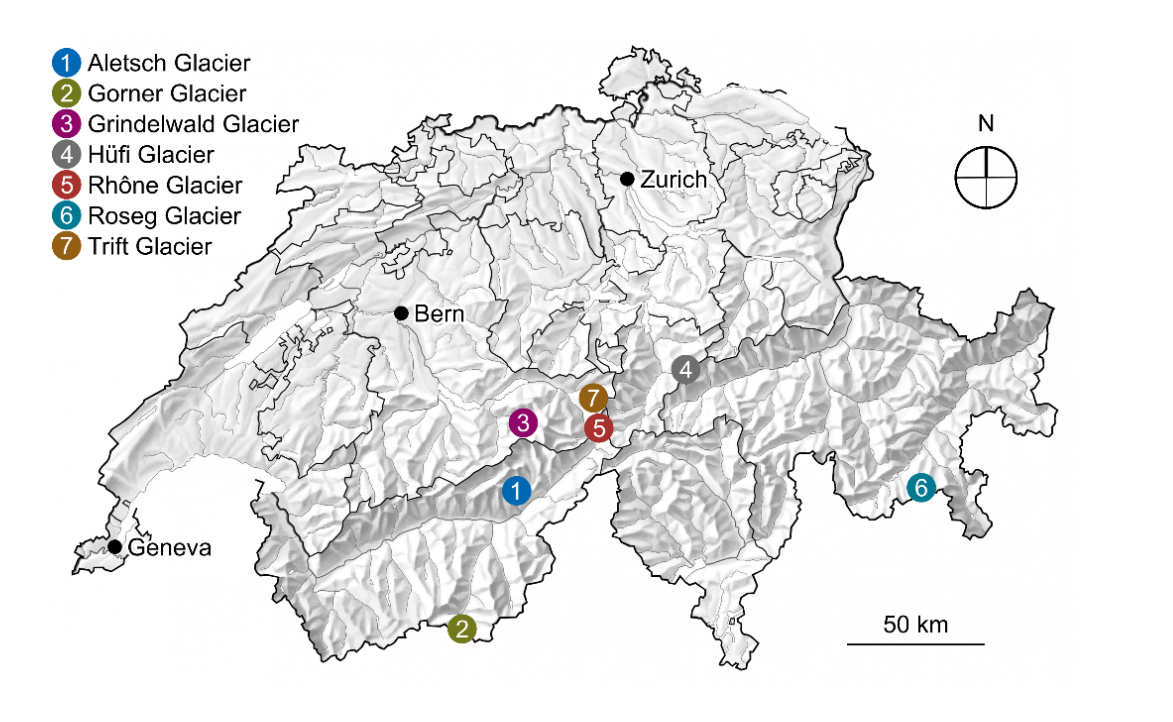

As they shrink, the glaciers are freeing up new areas that may be ideal for siting dams and reservoirs – for example, at the glacier “tongue”. In the Swiss Alps, there are thought to be about 60 such sites, seven of which are particularly promising, according to a study by the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich.

The new facilities could increase hydro-electric production during the winter, thus helping to reach the goals set in the government’s Energy Strategy 2050External link, researchers believe. Man-made lakes could actually play a part in keeping down the risk of natural disasters like floods or landslides, and function as water reserves in time of drought. “These new reservoirs will have to be multifunctional and provide not only hydro-electric production, but also irrigation of agricultural land,” Schaefli believes.

There is one problem, however: almost all the potential sites for reservoirs are within nature zones of national importance or ones listed by UNESCO, which makes it difficult to envisage large-scale building projects. One exception is at the Trift glacier, in the Bernese Alps, where the Oberhasli power company (KWOExternal link) is planning a new reservoir with a price tag of CHF400 million ($404 million). Pro Natura and WWF are already onside, but there are still those who are opposed and want to preserve the remaining alpine landscape.

Risky investment

Whether or not such projects are able to win approval, Axpo is reluctant to invest in harnessing glacier lakes for power. Although they have potential, and although there are subsidies for hydro-electric power generation, the uncertainty of future electricity prices and the long amortisation periods (60-80 years) make this kind of investment risky and not very profitable, notes company spokesman Walther.

Forgetting the “impractical” idea of using atomic power to increase hydro-electric production, more realistic models will be used in the future to ensure Switzerland’s electricity supply. They will be particularly needed from 2050 on, the year in which the country’s nuclear power stations are to be shut down for good.

Thanks to the nature of its terrain, the large number of waterways and abundant precipitation, Switzerland has ideal conditions for harnessing hydropower. The main cantons producing this kind of power are Valais (27% of national production), Grisons (22%), Ticino (10%) and Bern (9%).

For the operators of hydro-electric power stations, the biggest challenges are falling electricity prices, tougher restrictions on residual water and opposition from environmental organisations, which are against raising the level of existing dams and building new power stations in nature zones.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.