Who shows us how to live – Federer or Ronaldinho?

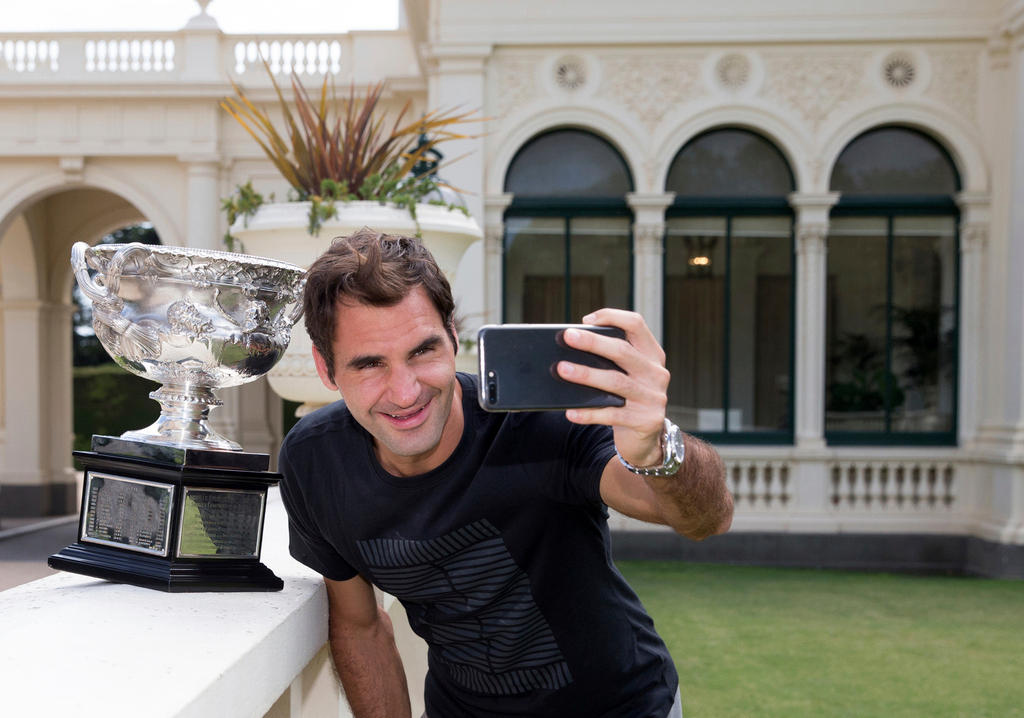

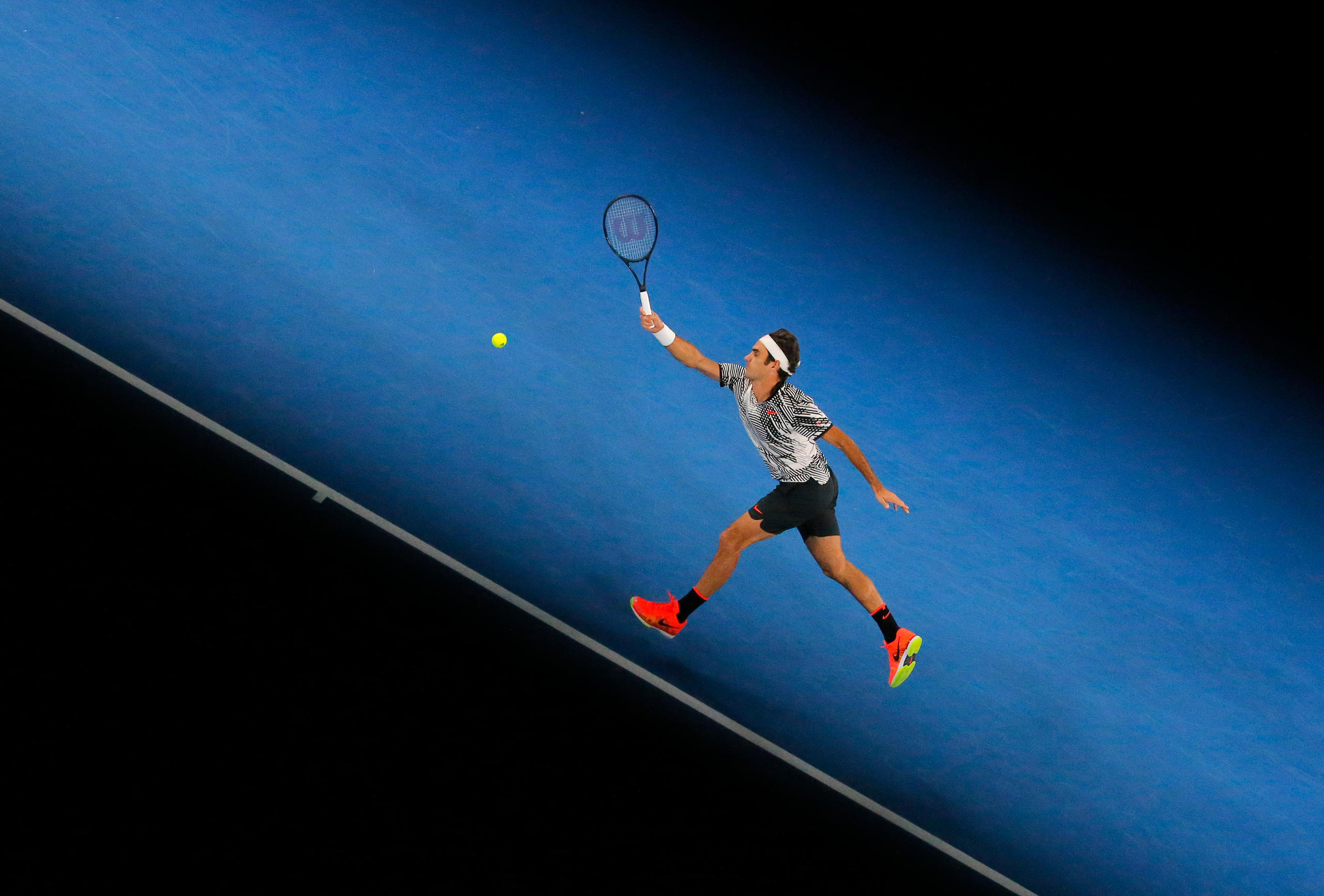

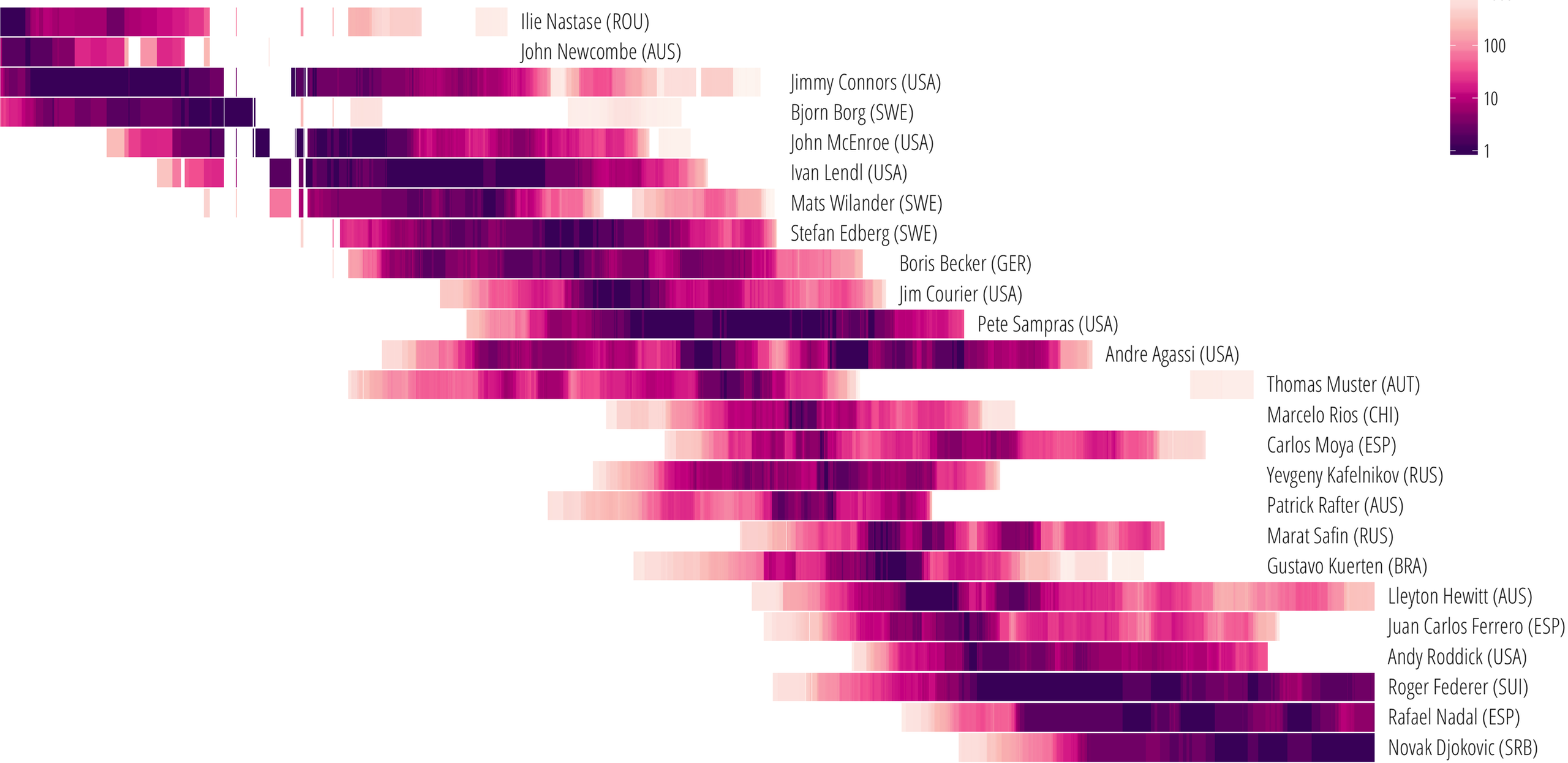

In January, Roger Federer won his 20th Grand Slam at the age of 36. It was his third title in a late-career comeback that beggars most sporting comparisons, leaving you to reach for Philip Roth’s 1990s revival as a truer parallel. Now free of injury, the Swiss could soon become the oldest number one in the history of the men’s tennis rankings, which he first topped in the week that Facebook went online.

Also in January, Ronaldinho retired from professional football at 37. There was no autumnal resurgence for him, just the prolonged winding-down of a luminous gift. A decade has passed since he was central to the world game. Europeans who recall the Brazilian’s mid-noughties miracles for Barcelona might have assumed that he had quit long ago.

More

Financial Times

External linkThe two most lavish talents of their sporting generation, certainly the only two who had it in them to make me involuntarily laugh, stand for different ways of going at life.

Federer is what students of decision-making call a maximiser, always striving for the best possible. He had the riches and titles to justify mid-career relaxation, but suffered to achieve more. It takes monastic discipline to sustain primacy, not just competitiveness, in a sport whose biomechanical demands make such short work of joints and cartilage.

I have met versions of him in business, still waking before dawn to squeeze efficiencies from their supply chain long after their fortune has crossed from the unspendable to the uncountable. The spoils of their work mean less to them than the work itself.

Ronaldinho is more of a “satisficer”, one who aims for a certain threshold (in his case, an extraordinarily high one) rather than more and ever more. It was at 26, when he added the Champions League to his World Cup and his Ballon d’Or, that coaches sensed his professionalism slackening in a haze of late-night parties. Barcelona phased him out at the age most players enter their prime. He went on to decorate AC Milan and the Brazilian league, but the downward arc was unmistakable, and – for football fans – tragically premature.

Don’t worry, be happy

The two careers invert our romantic idea of where drive comes from. Stereotypically, it would be the polished native of Basel, where the world looks for financial regulation, who could be expected to lack a certain hunger, and the bereaved son of Porto Alegre who would burn with motivation. The assumptions of class even attach to their sports, with tennis linked to privilege (tell the eastern Europeans that, or indeed the Williams sisters) and football to the global street.

The two careers also leave us to wonder which is the “right” way of living. Federer and the ever-smiling Ronaldinho seem about as content as each other. As for the general population, however, the scholarly verdict is that satisficers tend to be happier than maximisers. Whether their decision is the purchase of a kettle or the management of superlative talent, they are less prone to regret and second-guessing.

In his 2004 book on the subject, The Paradox of Choice, the American psychologist Barry Schwartz made the case for satisficing. The most unfakably content people I know are masters of “good enough”. They had a picture of a nice life and entered a kind of cruise control once they made it real. Their careers have slightly undershot their maximum capabilities. They might not be married to the most ardent love they have ever known. But they are so at ease with their lot that they will confess these things in good cheer (out of their spouses’ hearing range).

Conversely, I have met globe-bestriding achievers who reek of regret at things not done, opportunities missed, prizes withheld. These people make the world go around but you do not leave their presence with much envy. Entrepreneurs and retired politicians are classics of this haunted, restless type.

It is a skill not to move the goalposts as success pours in, to avoid invidious comparisons with what other people have or do. It is a skill to “not worry about the possibility that there might be something better”, as Schwartz puts it. What disappointed fans see in Ronaldinho as waste or indulgence is itself a kind of mental discipline – perhaps the highest kind.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2018

https://interactive.swissinfo.ch/2018_01_28_federer20/en.html#/enExternal link

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.