Making crowdsourcing work for the disabled

Shaju Cherian is a person with rare talents - one in ten million in fact. A Swiss-funded project could leverage his skills to help disabled people in poor, rural India.

Cherian is one of only three trained and experienced prosthetists and orthotists – professionals who design and fabricate devices to help disabled people – in the state of Kerala, which has a population of almost 35 million.

But on this day, he’s got company. Unusually for the 40-year-old, he is in the midst of a group of around 30 people who share his skills, passion and vision. Cherian is a participant at the Enable Makeathon, a two-month crowdsourcing challenge organised by the Swiss-run International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to encourage innovative solutions for disabled people in rural areas. Fifteen on-site teams working out of the Indian city of Bangalore and 13 online ones scattered around the world are competing for prizes worth $50,000 for the three best inventions.

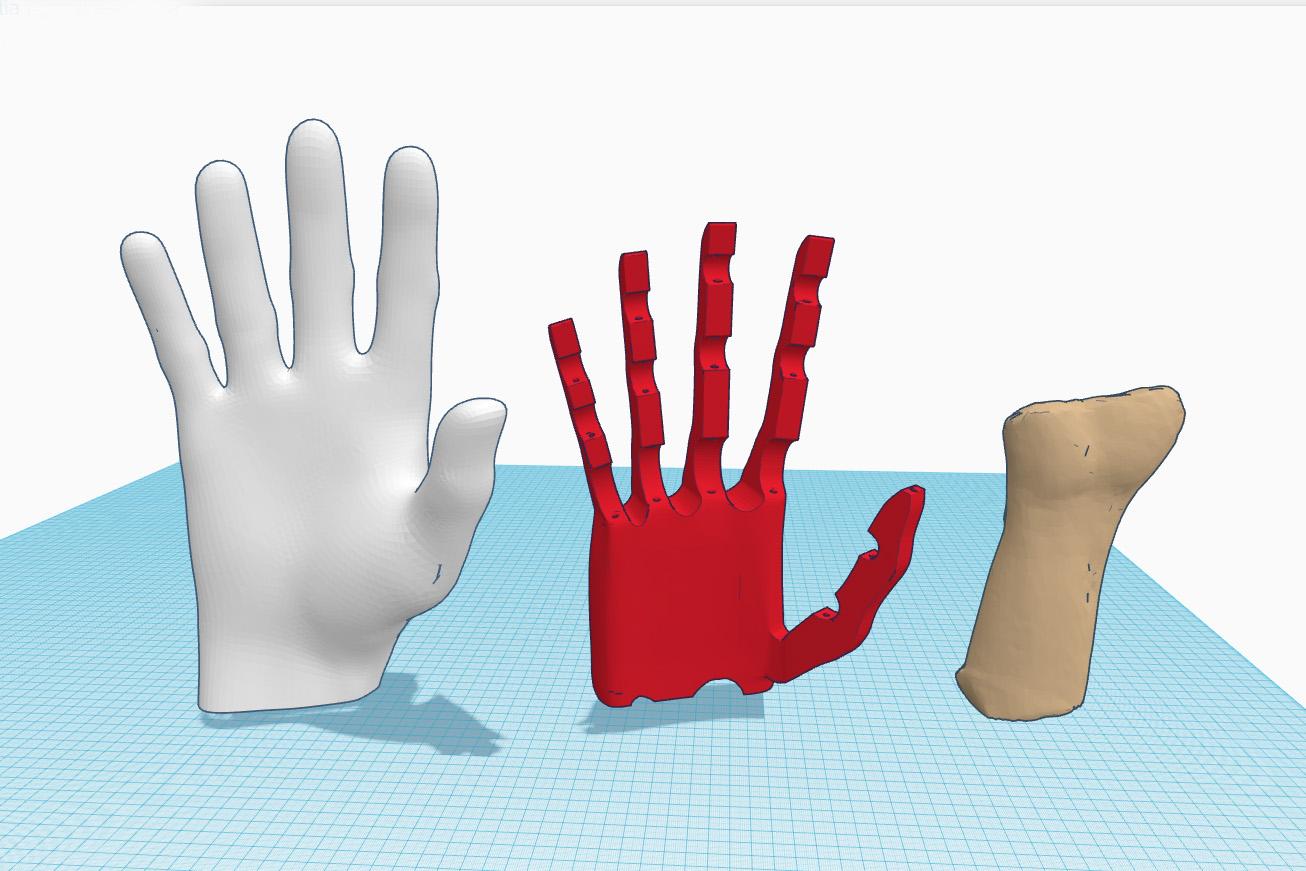

Cherian’s contribution to the competition is a prototype for a device designed to help those unable to use their arms for eating or grooming themselves.

“We came across a man who couldn’t bend his elbows and as a result he couldn’t eat like normal people,” he tells swissinfo.ch. “He was forced to eat like a dog does and this was difficult for us to see.”

More

Affordable innovation for the physically challenged

Rural challenge

According to the 2011 census, more than 20 million Indians are disabled. Over 70% of them live in rural areas.

In December last year, the Indian government launched its “Accessible India campaign” that aims to make government buildings, airports and train stations accessible to the disabled by 2019. However, the focus of this campaign is on major cities and is therefore more likely to benefit those living in urban areas.

“You can’t do much in a wheelchair in rural India,” says Mohan Sundaram of the Association for People with Disability APD, which is also the disability partner for the Enable Makeathon. “In urban areas there are convenient options to travel from home to the workplace but in a village one is completely dependent on the public bus network which is not at all suitable for disabled people. This means they can’t work and therefore cannot live a dignified life.”

According to him, affordable mobility solutions along with investment in infrastructure in rural areas are vital for empowering physically challenged Indians.

“There are motorised wheelchairs that cost INR1.5 million [CHF22,615],” says Sundaram. “Even disabled people in urban areas can’t afford them, let alone those in rural areas.”

Another entrepreneur who is taking on the challenge of affordable mobility at the Enable Makeathon is Soham Ganatra from Mumbai. His team is working on a brain-computer interface for wheelchairs that will allow paralysed users to control their chairs using brainwaves. The technology is already available but is prohibitively expensive.

“Higher end sensors found in research labs cost several hundreds of thousands of rupees but our sensor costs only around INR30,000,” says Ganatra.

But even with the significant cost cutting achieved by Ganatra’s team, it is likely to end up being too expensive for rural India.

“In the West products are designed with aim of providing users with 100% independence at any cost,” says Sundaram. “Here if you can produce something that gives the disabled 80% independence at 10% of the cost it is a wonderful thing for us.”

Viable solutions

“Right now there is a low uptake of existing products on the market because of low quality, unsuitability to local needs and high price of better quality options,” says Tarun Sarwal of the Geneva-based ICRC.

Tackling disabilities is one of the core areas of the Swiss-based humanitarian organisation as part of its programme for rehabilitating victims of land mines in conflict areas. Sarwal hopes that around eight to 10 of the prototypes become viable products and are made available to people at an affordable rate in rural areas. According to him, crowdsourcing platforms like Enable Makeathon could help organisations like the ICRC reduce operating costs.

“From what I have seen so far, I don’t think anybody could have obtained such a wide range of viable solutions for such little money,” he says. “We want to try find ways to do this not just for disability but also in the areas of water and sanitation for displaced people.”

Sarwal says that ICRC chose to experiment in India because there is expertise in catering for the bottom of the pyramid through developing low cost devices. They were also drawn to the innovative spirit exemplified by the large number of hackathons, makeathons and social impact investment fairs that take place in big Indian cities like Bangalore.

India is good testing ground for such products, according to Prateek Khare of swissnex India – a Swiss government funded initiative to promote science and innovation exchange with India – that is also an event partner.

“If you can solve local problems in India, you are creating solutions for another billion end users outside India as well,” he says.

While there is no shortage of innovative ideas at the Makeathon, transforming them into a viable product for users with extremely limited purchasing power is a tough ask. Besides coming up with a product, participants also have to come up with business models that ensure the long-term financial sustainability of their designs.

Some participants plan to offer their products to rural users at a loss and then try to recoup their costs through corporate social responsibility (CSR) laws that obliges companies with a certain turnover to contribute 2% of their average net profits towards social development measures.

Others want to design their product for multiple applications in order to subsidise the costs for disabled users. For example, Neha Govardana is helping develop a low cost system to identify abnormal gait using an off-the-shelf Microsoft Kinect camera. This cost-effective solution can also be applied to sports rehabilitation. Many of the other prototypes in the competition are useful for the elderly too who also suffer from reduced mobility.

Sundaram from APD, who is disabled himself, is skeptical about purely market-based solutions. According to him, the commercial market in India is very small and hence profitable only when it comes to expensive, high-end products. He is convinced that investment in solutions for the physically challenged will only come when it is viewed from the correct perspective.

“Right now it is seen as something that gives the disabled dignity and not as a measure that will benefit the country in terms of productivity,” he says. “Addressing disability early in life and including the disabled population into the productive mainstream means that the country spends less on disability in the long-term.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.