Evolution on a Swiss scale

It seems like we’re always hearing the buzzword ‘biodiversity’ and how important it is…but does it really matter if we lose a species here or there? Research on one of Switzerland’s most popular fish provides new insights into the consequences of dwindling diversity.

The chances are good that a visitor to French-speaking Switzerland, famished from wandering cobbled city streets or winding hiking trails, might dine on féra – known in English as whitefish – in a local restaurant. Affordable, versatile and mildly flavoured, this unassuming fish is a member of the salmon family, and is a common fixture on menus all around Lausanne, Vevey, Montreux, and Geneva.

Although “féra” originally referred to a single native Lake Geneva fish called Coregonus féra, that species has not been seen in Switzerland since 1920 and is now believed to be extinctExternal link. Today, the name refers to 15-20 different species, which vary widely in shape, size, and habitat preference.

Their considerable species diversity and ecological importance have made whitefish among the most-studied fish in science, where they are referred to by yet another moniker: their genus name, Coregonus.

But despite the array of Coregonus found in Swiss lakes today, it’s only a fraction of the wealth of varieties that once existed: over the course of the second half of the 20th century, a form of pollution known as eutrophication wiped out some dozen Coregonus species native to Switzerland.

Ole Seehausen and his colleagues at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (EAWAG) first linked the decrease in whitefish species to eutrophication back in 2012, in a paper published in the journal NatureExternal link. Now, for the first time, they have published data suggesting that this drop in Coregonus biodiversity could also hinder the efficiency of lake ecosystems when it comes to producing fish.

Simply put, Swiss lakes that were hit hardest by eutrophication in the past, are less efficient at converting food into fish today.

“We looked at cantonal fishery catch statistics from across all the lakes, and we found that lakes that didn’t suffer significant damage to their whitefish biodiversity yielded the best fishing catches for a given amount of food,” Seehausen tells swissinfo.ch.

The research was published in February by the Royal Society (UK)External link.

Too much of a good thing

Eutrophication occurs when excess nutrients and minerals – particularly phosphorus – enter lakes from sewage, chemical or fertiliser runoff. While too many nutrients might not sound like a serious problem, it actually sets off a chain reaction that can upset the delicate balance of life below a lake’s surface.

Excess phosphorus promotes algae growth, and when the algae die, they sink to the bottom of the lake and are consumed by microorganisms. But those microorganisms consume a lot of oxygen, sometimes using up so much that there is not enough left for larger organisms that need it, too – like fish and their eggs.

Often, the upshot of this domino effect is that certain lake habitats are no longer able to support other kinds of life. And once these habitats disappear, so do the species that evolved to live in them.

In Switzerland, the eutrophication of lakes was at its worst between the 1950s and 1980s. Since then, conservation interventions – notably the introduction of a phosphorus removal step during sewage treatment and the banning of phosphates in laundry detergents – have helped to greatly reduce lake phosphorus levels. But the ecological consequences are still reverberating, decades later.

“A lake can physically recover relatively quickly if you make sure that nutrients are better retained in sewage treatment systems. But the native diversity of organisms such as whitefish does not return so fast,” Seehausen explains.

Open wide

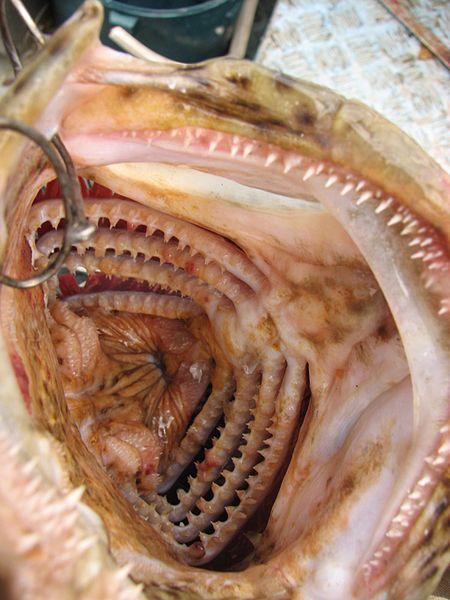

To show the impact of lowered biodiversity on fishery production in Swiss lakes, Seehausen and his colleagues took a second look at the data from their 2012 paper, which focused on gill raker measurements of different Coregonus species.

Gill rakers are tiny spikes made of cartilage or bone that protrude in rows from the inside of a fish’s throat. They vary widely in size and number depending on the species’ preferred food source: Coregonus species with sparse, robust rakers tend to sift through sediment at the lake bottom for mud-dwelling organisms, while those with finer, denser rakers are better at filtering food particles (plankton) directly from the water.

Using these gill raker variations as an indicator of Coregonus diversity, the EAWAG team then compared those data with cantonal statistics on professional fishing catches in different Swiss lakes.

They found that lakes hosting fish with a narrower range of gill raker variation due to severe eutrophication in the past (like Lake Geneva), produced four- to five-fold fewer fish per unit of food than lakes that had experienced less eutrophication – and therefore less biodiversity loss (like Lake Thun).

And this makes intuitive sense: one could imagine that a lake with two different Coregonus species living in it would be able to produce fish more efficiently than a lake with just one type, as each species’ unique adaptations would allow them to exploit different food sources without competing with one another.

New biodiversity angle

The EAWAG researchers call this intertwined relationship between human, fish, and lake a “possible co-evolutionary feedback loop”. And it’s a relationship that has not been well understood until now: while there is already plenty of data linking biodiversity and productivity on land, Seehausen says this study is one of the first to show evidence of this phenomenon in lake fish communities.

So what do these results mean for the human element of this feedback loop?

“Be very, very careful with your biodiversity – look carefully at what you have, and make sure you retain it,” Seehausen says.

Fishing in Switzerland

The Swiss are eating more fish: in Switzerland today, people eat roughly 8.8 kilogrammes of fish per person annually, compared to just 6.4 kg in 1984. The vast majority of fish consumed in Switzerland is imported, but of those fish that are local, Coregonus account for about 60% of professional catches. In 2014, that amounted to a harvest of just under one million kilogrammes, according to the Swiss Federal Office of StatisticsExternal link.

A species explosion

Seehausen and colleagues at EAWAG and the University of Bern published another paper in February in the journal Nature CommunicationsExternal link documenting a different – but closely related – phenomenon in fish biodiversity. They solved a scientific mystery by explaining the evolution of an unprecedented 500 species of small, perch-like fish called cichlids in Lake Victoria, East Africa, over the past 15,000 years. The evolution of such a huge number of species, they found, was made possible through a perfect combination of hybridisation and plentiful opportunities for habitat specialisation. The study’s first author, Joana Meier of the University of Bern, summed it up this way: “It’s similar to the way the recombination of parts from Lego tractor and aeroplane kits could generate a wide variety of vehicles.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.