Politicians to weigh human dignity in research

Human research is high on the agenda when the Swiss parliament begins its regular three-week autumn session on Monday.

One of the sticking points of the debate is likely to be human dignity, or more precisely scientific experiments on children and other people who are unable to act or judge for themselves.

The cabinet said preserving human dignity must come before research, when it presented its draft for the new constitutional article a year ago.

Interior Minister Pascal Couchepin argued scientific advances in recent years into ethically complex areas – including the creation of biobanks to store people’s DNA – made the introduction of a federal law an urgent necessity.

Nationwide regulations govern some areas of human research, including reproductive medicine and genetics, but the 26 cantonal authorities are autonomous in most cases.

Heated discussion is expected on the extent to which limitations should be imposed on research involving people who cannot take decisions alone, including children and the mentally handicapped.

“It would be a mistake to forbid research on such people. It would make it impossible to develop future treatments and specific therapies for the most vulnerable group of people,” said Verena Schwander.

Children and adults react differently to the same medicines, according to Schwander, a senior member of the Swiss Federation of Psychologists and one of the experts involved in drafting the proposal to parliament.

To avoid abuse, the new law insists that assent for participation in research is given by legal representatives of people with limited cognitive powers.

Benefits

Experts are keen to ensure that the risks attached to experiments are kept as low as possible, particularly if the test person will not benefit directly. But those undergoing tests should still have the opportunity to contribute to medical advances for society.

However, Kurt Seelmann, a law professor at Basel University, says the draft fails to define the risks for an individual, and to make it clear when the testing is for the benefit of society rather than their own benefit.

He says it is incompatible with law to oblige people to be involved in experiments for the benefit of others, particularly if the person concerned cannot express his or her opposition.

“Nobody is obliged to donate blood to save lives if they walk past the scene of an accident,” said Seelmann.

He welcomes the draft proposals but calls for an amendment to ensure that physical integrity is not damaged.

Ethic rules

On a political level, opposition to the draft article on human research is likely to be limited mainly to the Swiss People’s Party.

The rightwingers argue it is superfluous to enshrine in law the notion of informed consent to experiments on human research. They say this area is covered under the European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine.

But Josiane Aubert, speaker of a parliamentary committee on research and culture, hopes ethical rules will be listed.

“I don’t think it is good enough to stipulate that the federal authorities can legislate on the matter. We must also outline the preconditions for human research.”

Aubert adds that cantons define their own rules and regulations.

“Many of them set up ethics committees and research institutions and hospitals have developed guidelines to avoid infringing human dignity.”

But she says it is important to set up standardised rules on a nationwide level.

Legislation often lags years behind practical research. The first Swiss law on medically assisted procreation came more than 20 years after the birth of the world’s first test-tube baby, Louise Brown in Britain.

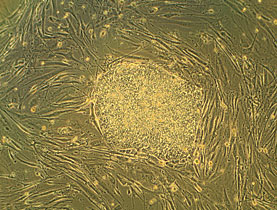

Similarly Marisa Jaconi, a biologist at Geneva University, started her research into stem cells years before Swiss voters approved a law in 2004.

swissinfo, Urs Geiser and Doris Lucini

The Federal Health Office defines human research as not only that involving persons but also experiments on human embryos and foetuses and biological material of human origin such as tissue, cells, and bodily fluids.

It also includes research on deceased persons and studies using personal data.

Research on humans is only partially covered by legislation at the federal level.

The main areas include clinical testing of drugs, transplantations, professional secrecy in medicine and public health, the handling of data, gene technology and stem cell research.

In other areas, Switzerland’s 26 cantons are responsible for legislation on research on humans.

The Federal Health Office notes that regulations differ from canton to canton.

The accord aims to preserve human dignity, rights and freedoms, through a series of principles and prohibitions against the misuse of biological and medical advances.

The interests of human beings must come before the interests of science or society, according to the convention.

It lays down a series of principles and prohibitions on bioethics, including medical research, consent, right to a private life and information, organ transplantation.

It bans all forms of discrimination based on the grounds of a person’s genetic make-up and allows the carrying out of predictive genetic tests only for medical purposes.

The Council of Europe adopted the agreement in 1997. Switzerland signed in 1999, but the convention was only ratified in July 2008 and is due to come into force in November.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.