Switzerland’s safety net must be there for all

Images of several thousand people queuing each weekend to receive food parcels in wealthy Geneva have circulated in the international press recently. The working poor and undocumented migrants in Switzerland have been hard hit by the coronavirus pandemic. A group of concerned citizens in Geneva is calling for respect for migrants’ fundamental rights and for regularisation.

For many foreign observers, the fundamental right to food is something that has always been observed in Switzerland.

Fundamental rights are not only at risk but are sometimes ignored

Yet recent distributions of food aid by the local authorities, NGOs and private associations at the Vernets sports centre in Geneva seem to have taken the international press External linkby surprise.

For almost a month now this trend has been visible and continues to grow. In the international capital of human rights, Switzerland’s second-biggest city, and in a country often praised for its excellent economic and social organisation, part of the population is in dire need of food. People who previously did not believe fundamental rights to be at risk in our country are suddenly aware that food is a basic right and that, if necessary, it is the community’s responsibility to guarantee it.

More

Who’s at risk of poverty in Switzerland?

Guaranteeing fundamental rights

People without legal status, so-called undocumented migrants, represent more than half of the people receiving food at Les Vernets. However, those who have been working with this population for years and are familiar with their plight know that in Switzerland—yes, even here—fundamental rights are not only at risk, but are sometimes ignored. In reality, we are often incapable of treating all human beings like human beings. If it were not for the startlingly depressing spectacle of Vernets, we could perfectly well continue to shut our eyes to the fact that thousands of people in Geneva, and an estimated 100,000 “sans papiers” in Switzerland, do not even dare report an assault or a theft. The rule of law does not apply to everyone; it applies first and foremost to those who hold the right papers.

The overwhelming majority of our fellow citizens probably feel that it is our duty to ensure everyone has access to justice, food, healthcare, etc. People quite often insist that in Switzerland there is always a right to report abuse, to get treatment in hospital and to be helped if you lose your job. The facts, however, tell a completely different story. The lack of solidarity and of the opportunity to assert one’s rights are starkly revealed when society has to face extraordinary constraints such as what we are experiencing with Covid-19. Unsurprisingly, anyone who is vulnerable or in a precarious situation is the first to suffer in such circumstances.

Some authorities and organisations active in the fields of social assistance and integration started to notice and deplore such lawless no-go areas a long time ago, and have been trying to do something about them. Thirty-five years ago, Dominic Föllmi, a Geneva state councillor, personally accompanied a young girl without legal status to school for the first time. Since then, following Geneva’s example, the fundamental right of children to attend school has been respected in many parts of Switzerland. Elsewhere, Geneva University Hospital’s Mobile Outpatient Consultation Unit for Community Care (CAMSCO) also provides medical care, regardless of the patient’s status. But the fear of denunciation and deportation means that other fundamental rights – such as the right to a private and family life, proper access to justice or protection against exploitation at work – are in practice not guaranteed. Notable efforts are being made by some authorities and a large number of NGOs, and they should be welcomed. However, they can be seen as an uncoordinated patchwork or, worse, amateurish. In view of these examples and of the plight of those queuing up at Les Vernets, it is obvious that the only approach that will guarantee fundamental rights are respected is the regularisation of undocumented migrants.

Regularisation is key, but the fact that a number of people queueing up at Vernets actually have regular papers shows that it is not sufficient. What is really needed is to eliminate precarity more generally, the permanent threat of suddenly descending into poverty. Many people go to Vernets because they do not dare take advantage of the welfare payments they are entitled to, for fear of losing their residence status. For many foreigners, not claiming welfare payments is a condition for the renewal of their work or residence permit. These people are therefore caught in a Catch-22 situation: either starve, or lose the right to work and earn money to live on. Unless the conditions that create such precarity are changed, for those with or without papers, certain fundamental rights will continue to be ignored.

Regularisation is possible and necessary

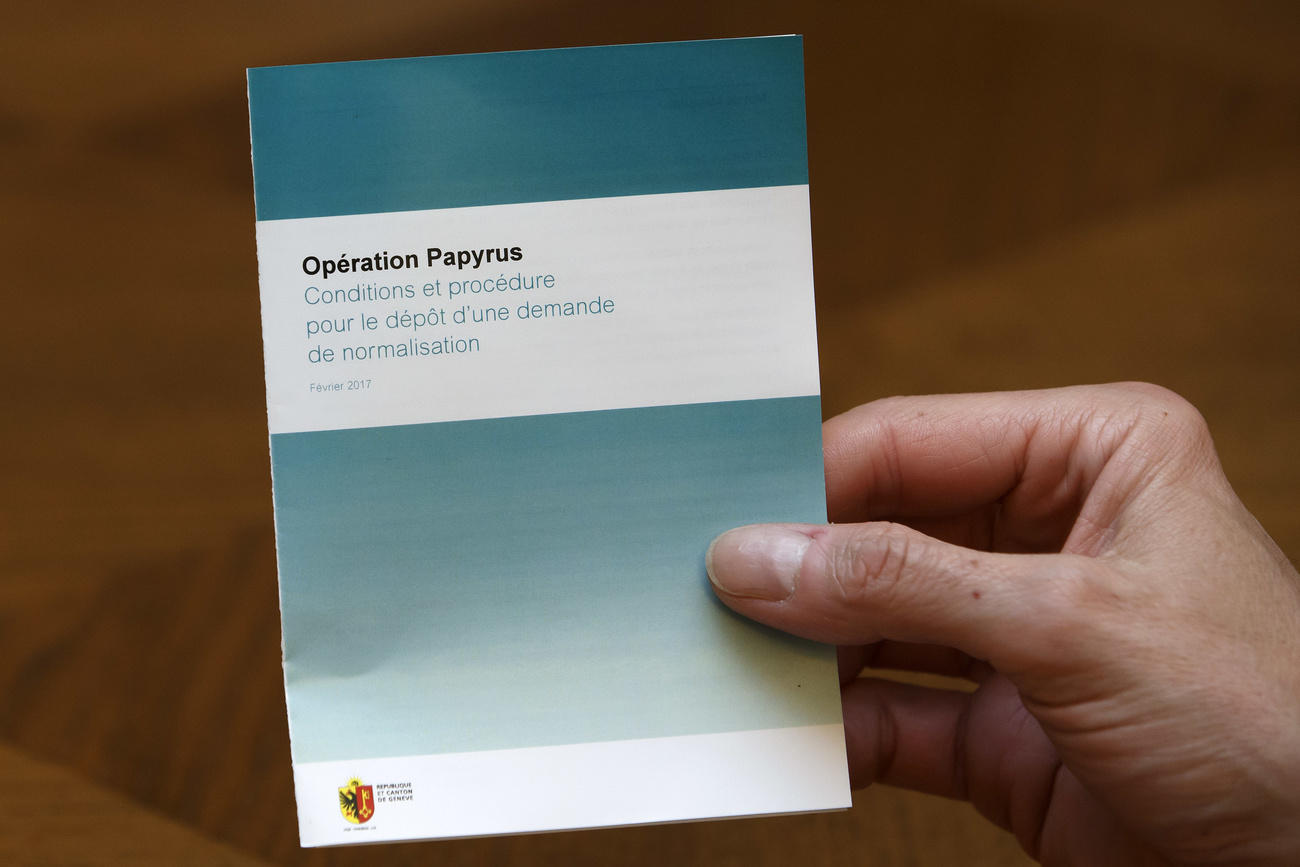

Not only is regularisation necessary, but recent experience has proven that it is possible. Prior to the Papyrus pilot project (2017-2018) [to regularise long-term undocumented migrants in Geneva], the argument was often heard in some circles that regularization would attract other people and illegal immigrants would flock en masse to Switzerland. But the results of the Papyrus scheme, scientifically evaluated by experts, proved that this was not the case. Today, we don’t need a continuation of Papyrus. Papyrus was a test that was limited in time and scope. We need an approach that makes sense both in human and legal terms. It consists of regularising undocumented migrants on the basis of clear and predictable criteria. And the recent moves to regularise undocumented migrants in ItalyExternal link and Portugal during the coronavirus crisis prove that another policy is possible.

On May 25, the Geneva cantonal government adopted an emergency draft law aimed at providing financial support to vulnerable residents in Geneva who are struggling amid the coronavirus pandemic. The measure is aimed at undocumented migrants, people who are not entitled to welfare, and others who did not receive earlier cantonal or federal Covid financial support.

To make a claim, the person must be able to prove that they have lived in canton Geneva for at least one year and have been employed for at least three months preceeding the partial lockdown that came into effect from mid-March.

The government has set aside a budget of CHF15 million. The proposal still needs to be approved by the Geneva parliament.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of swissinfo.ch.

More

‘Switzerland is going to face an unimaginable level of poverty’

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.