Are the Swiss having second thoughts about capitalism?

The extraordinary series of political initiatives on pay rates which are being put to Swiss voters is the sign of a rank-and-file “rebellion” against fat-cat salaries for top managers. But the free market is still generally accepted, say two academics in the field.

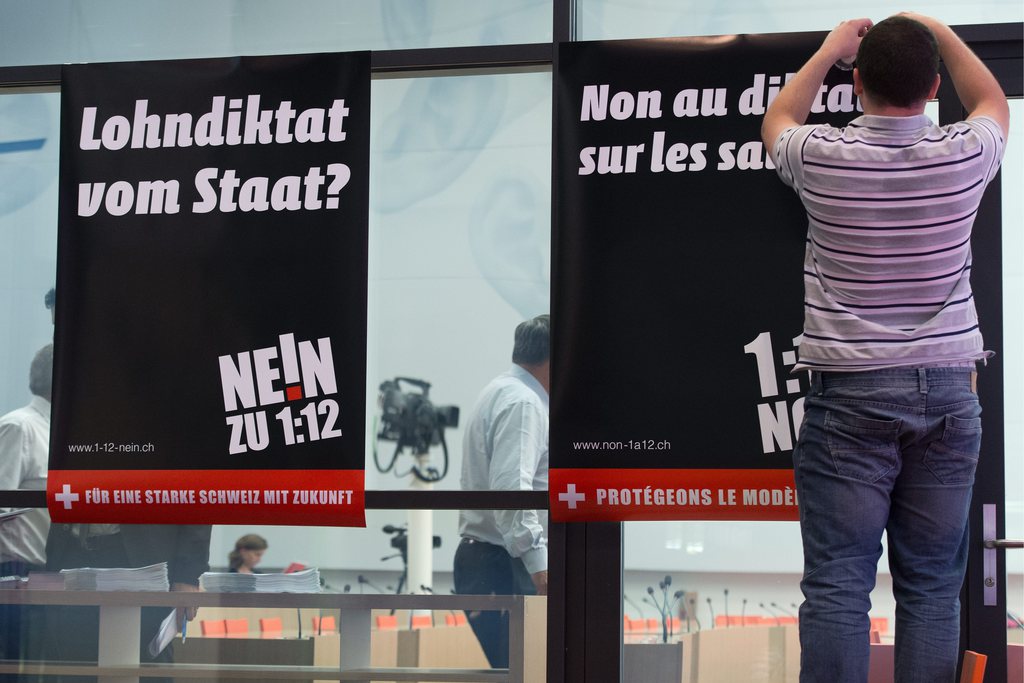

The shock-waves after the carrying of the popular initiative “against rip-off salaries” in March 2013 have not yet abated, but on November 24 there is to be a nationwide vote on another proposal to put the brakes on the pay of top managers. This is the initiative “1:12 – for fair pay”, which proposes that the highest wage paid by any company be no more than twelve times the lowest wage it pays. Next year, a further initiative could set a minimum legal wage for Switzerland.

Demands for more equitable pay rates have traditionally come from the left, but in the last few years they seem to have won favour with a broad spectrum of voters.

According to the annual ratings put out by the Travail Suisse trade union grooup, in 2012, the widest pay gap in Switzerland was found at Roche, where CEO Severin Schwan, at CHF15,79 million francs ($17,50 million), made 261 times more than the lowest-paid employee of the Basel pharmaceuticals conglomerate. In second place was Nestlé, where CEO Paul Bulcke made CHF12,608 million, or 238 times the lowest salary paid by the food giant. In third place was ABB where the tidy sum of CHF10,158 million paid to CEO Joe Hogan amounted to 225 times the wage of the lowest-paid employee.

Imported system rejected

“Citizens have rebelled against a system of pay imported from the English-speaking world in the last twenty years in the wake of globalisation”, Rafael Lalive, who teaches economics at the University of Lausanne, told swissinfo.ch. This system is linked to “development of financial products, such as ‘call options’, which have made it possible for top managers to receive fabulous salaries”, he explains.

In Switzerland this system has created not just popular discontent, but also “severe tension between home-grown industry on the one hand, and the big banks and multinational exporters on the other”, notes Tobias Straumann, who teaches economic history at the universities of Zurich, Lucerne and Basel.

The traditional model of Swiss business is based on social responsibility. Home-grown entrepreneurs “feel that the élite of the big companies are profiting from Switzerland, living and working here, and earning whopping salaries, but have no interest in the country. They find this unacceptable.”

The objection is not to wealth itself. “If a businessman is very rich, but people have the feeling that he takes care of his company and his staff and that he is connected to Switzerland, his wealth is considered a right”, explains Straumann.

More

The pros and cons of the 1:12 initiative

Minder initiative

The initiative promoted by independent businessman Thomas Minder, which was approved in a popular vote last March, reflects this growing criticism. Yet it does not involve a questioning of the free market itself, both economists believe.

“The Minder initiative put a stop to a kind of freedom which was without justification. It took away from top managers of big companies the power to decide their own salaries and gave it back to the owners – that is, the shareholders. This now allows the free market to function better, because it allows the owners to sanction poor performance on the part of executives and reward good performance. It aims to bring back systems of pay that are more realistic, but without the government having to get involved with matters that really belong to the private sector”, says Lalive.

More

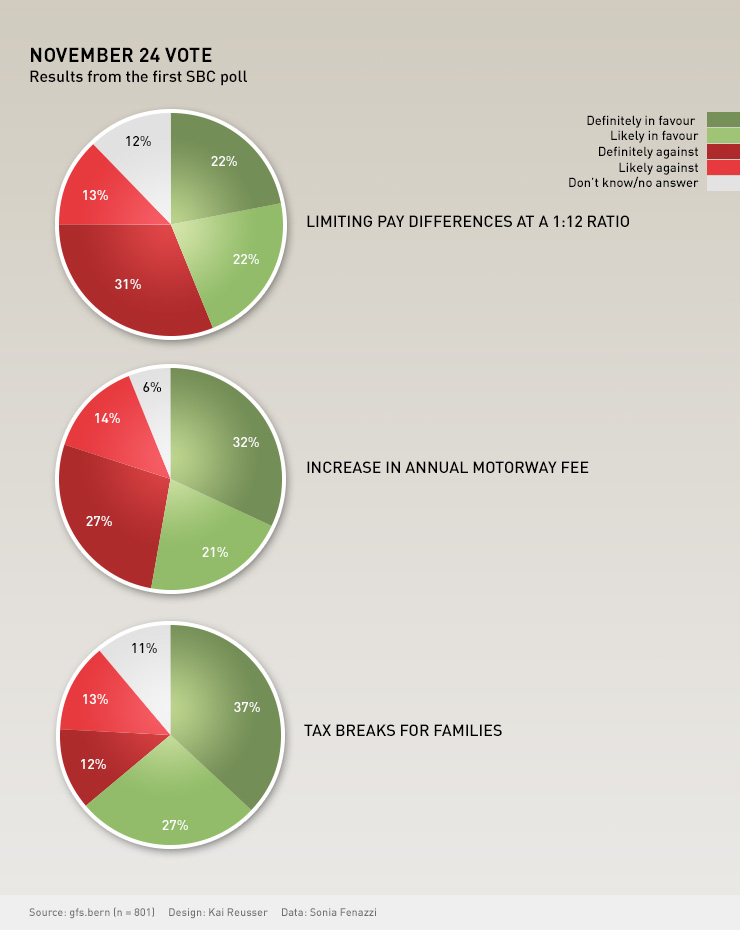

Poll results

Radical change in rules

This reveals a fundamental difference between Minder and the initiative “1:12 – for fair pay”, which would impose a legal ceiling on pay disparities. The government would then have to monitor its implementation. Just because of this aspect of government intervention in the private sector, the two academics believe that the proposal from the Young Socialists will not win a majority in the vote on November 24.

The initiative “would change the regulation of pay, the rules of business. And that is not what most Swiss want, for they tend to be liberal when it comes to the economy”, says Straumann.

The Swiss economy is working well, unemployment is low, and there are no major social problems. So the basis for a change in the system is just not there.

“Although the pay gap has widened in Switzerland too over the last twenty years, it has not grown all that much. It’s not like in the US and Britain, where inequalities have increased enormously – not just have the rich got richer and the poor poorer, but there has been a dramatic decline of the middle class, too”, notes Straumann.

According to the most recent data published by the Federal Statistics Office, in 2010 in Switzerland the average gross salary for a full-time equivalent was CHF5,98 per month.

The monthly average gross salary of senior management was CHF10,189 in the private sector and CHF16,519 in the public sector (federal government), and that of top managers was CHF22,755 in the private sector and CHF21,548 in the public sector.

One tenth of employees made less than CHF3,953 a month, and one tenth made more than CHF10,833.

Topic will stay on political agenda

“The social consensus is still intact in Switzerland. People are not angry like they are in the US and Britain. For that reason, the Young Socialists are not likely to get a majority for their proposal. I believe, on the other hand, that the theme of pay is not going to go away after this vote. It will still remain at the centre of political debate for quite some time”, Straumann believes.

According to fellow-academic Lalive, “we will have to wait for the Minder initiative to be applied for three or four years, to know if that will be enough to limit the explosion of pay. If the pay of top managers doesn’t go down, I think that there will be a slight majority in Switzerland for giving power to the government to limit rates of compensation. Right now it’s just too early for that.”

It also seems too early to predict the chances of the upcoming initiative for a minimum legal wage in Switzerland, launched by the trade union movement. But it is also important to distinguish the scope of this proposal from the radical change called for by the “1:12” initiative. As it happens, “there is already a minimum wage in many countries”, notes Lalive.

Here in Switzerland, the idea of a minimum legal wage has already been adopted at cantonal level by Jura and Neuchâtel. In cantons Vaud and Geneva, on the other hand, the voters rejected it. So the score is even – 2 to 2 – which makes a close contest likely between advocates and opponents of the idea at federal level. Yet even that prediction can only be tentative, because the four cantonal votes so far have been confined to French-speaking Switzerland.

The people’s initiative “against rip-off salaries” promoted by independent businessman Thomas Minder was approved on March 3, 2013, getting the nod from over 68% of voters in all cantons. It stipulates that the shareholders’ AGM is to decide each year on the amount of pay for the board, the executive and the advisory body of any publicly-listed Swiss company. It strictly forbids golden handshakes and advance payments to corporate leaders.

The initiative “1:12 – for fair pay”, launched by the leftwing Young Socialists, will be put to the electorate on November 24, 2013. The proposal is that in any company the highest salary paid cannot be more than 12 times the lowest. Salary here means “the total of payments (money, in-kind payments or services) awarded” by the company.

The initiative “to protect fair pay”, launched by the Swiss Trade Union Federation, is currently being considered by parliament. It calls for the introduction of a legal minimum wage of CHF22 an hour, which would mean a monthly salary of CHF4,000. This figure would have to be adjusted periodically to keep pace with wage and price developments.

(Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.