Public media and young viewers: are they flicking over?

One year after voters thumpingly rejected the idea of scrapping the licence fee, public broadcasters in Switzerland and beyond tackle the challenge of securing future audiences.

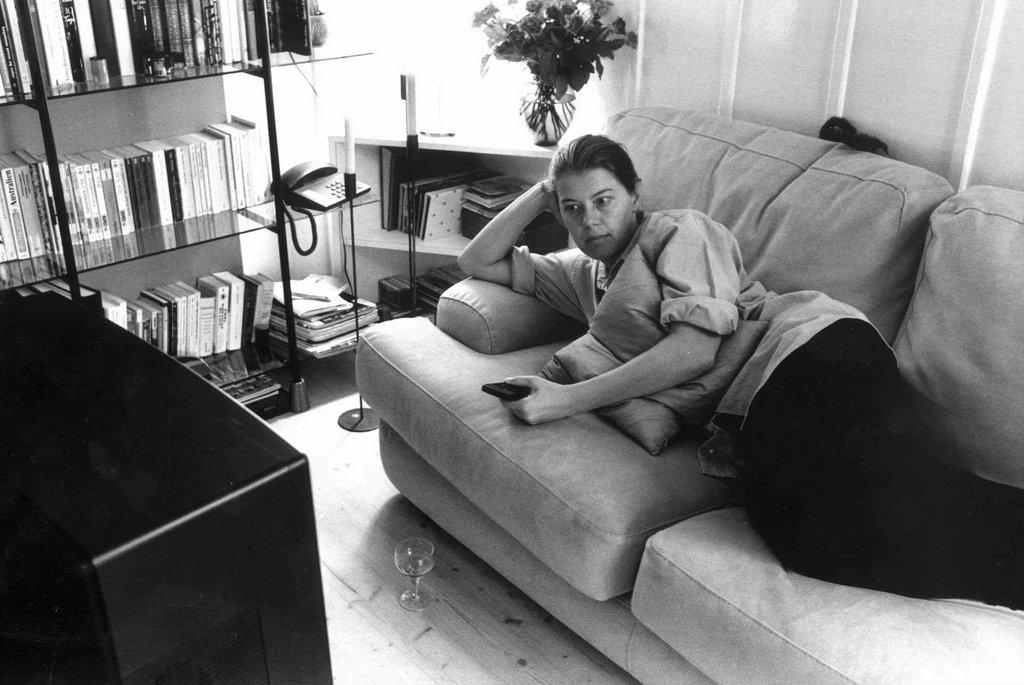

Cosy, warm, brain-dead, you’re tucked up on the couch after another day. On the TV, or some screen, your latest Netflix series is jumping kindly from episode to episode; you don’t even have to lift a finger. You check your phone. 19:30. Somewhere, in some other corner of the universe, the news is starting – SRF’s TagesschauExternal link.

Do you flick over?

One year after Swiss voters opted largely not to scrap the country’s public-funded state media system, the question still hovers. And as technology, media, habits, and content continue to shift faster than a journalist can keep up with them, the answer is still unclear.

On one hand, as the BernerZeitung reportedExternal link last week (in German), some things don’t seem to change. The most watched show via the Swiss Zattoo online streaming service – which accounts for 53% of all online streaming activity in Switzerland – is still the daily Tagesschau news bulletin; The Big Bang Theory is second, the newspaper says.

However, the report didn’t say which demographics are tuning into what. Where is the younger generation flicking? Though it’s wrong to exaggerate the generational divide, other studies that present a picture of shifting youth habits are the source of various headaches for the soul-searching public broadcasters in Switzerland and beyond.

More

On the road with Switzerland’s public broadcaster

Not on the radar

For one thing, according to the Reuters Digital News ReportExternal link, 18-34-year-olds in Switzerland continue to largely shun broadcast TV as a source of news in favour of online sites and social media; growing numbers are also prepared to pay monthly subscriptions to entertainment services, especially Netflix.

But the SBC, of which swissinfo.ch is a part, is not alien to online and social spaces. So why is it struggling to attract new eyeballs? After all, young people are generally in favour of public broadcasting (at 80%, under-30s were the biggest rejectors of ‘No Billag’); the Reuters report also found that public broadcaster content was the most ‘trusted’ in the country.

For Ulla Autenrieth, a media researcher from the University of BaselExternal link currently looking into this topic (see box below), it’s mainly a question of incentive and exposure.

Public service content is simply not on the youth radar, she says. Gone are the days of SRF or RTS being the go-to centre of the media universe; in the current, highly-competitive field, they are not reaching their targets.

Used to heading straight to Google or YouTube (interestingly, perceived as direct media sources rather than content aggregators), or having content suggested via social networks, younger users simply don’t consider public media, she says. When they do, they also don’t have the patience to trawl through websites like SRF.ch, which is less tailored towards a personalized experience than something like Netflix.

In short, the ‘pull’ strategy of the past, of passively attracting readers/viewers through quality content, is no longer possible. Now active ‘pushing’ – with all the filter bubbles and problems that it brings – is the only game in town. If you sit back with the attitude of ‘here we are, come and find us’, you are not working in the 21st century, Autenrieth says.

More

Study links shrinking local media landscape and lower voter turnout

A face-off between information and entertainment is also a factor. Submerged in cascades of series and social posts, newer generations are less willing, and less obliged, to tune into the drier informative features that public media is mandated to produce.

Is public service content boring? Of course, ‘boringness’ is subjective. But it’s usually boring people that make this observation; and it’s likely that for many – young and old – Breaking Bad is more interesting than news of, say, a Swiss trade deal with Indonesia.

Ultimately this is reflected in the fact that people in Switzerland are more and more likely to pay for Netflix and streaming services, but quite unlikely, even compared with other European countries, to pay for news and information (which they get at the bus stop in the morning anyway, courtesy of the free nationwide newspaper 20 Minutes).

Re-connecting with audiences

None of this is very new. But what’s it leading towards? A situation where the next generation agrees to fund public media and information then later ignores it? Or where public media tries to get up to speed by sensationalizing otherwise anodyne content?

Neither option seems great.

The first is a waste of resources in the short-term and a path to obsolescence in the longer. The second would fuel fears that democracy and rational debate are being undermined by an attention-driven media (another University of Basel studyExternal link recently found that periods of media frenzy in the US around sensational issues coincided with significant, but less exciting, political decisions passing through Congress).

Autenrieth doesn’t have a clear prescription. For now, she can only point to some examples of innovation and success in the print and online spheres, where ‘communities’ are starting to mobilize to fund quality journalistic reports and projects that interest them. The recently-launched RepublikExternal link in Switzerland is one example; the German KrautreporterExternal link is another, she says.

Like Gilles Marchand, Director-General of the SBC, she also mentions the possibility of investing in locally-produced Swiss content that could later be made available to viewers on more innovative and tailored streaming platforms. If you can’t compete with Netflix directly, then become your own version of Netflix, goes the logic.

But whatever the infrastructure that emerges, one thing that most agree on is that “only those who are well informed can make informed decisions”, as a 2017 ETH Zurich reportExternal link put it. In a democracy like Switzerland’s, where voters are called to the ballot box up to four times per year, that’s even more crucial.

On March 4, a year after the No Billag people’s initiative was rejected by Swiss voters, the SBC is co-organizing (along with BAKOMExternal link, FMECExternal link, and SACMExternal link) the International Public Media Conference (IPMC) in Bern.

Speakers, including media professionals from Switzerland and abroad, will address the role of public media in providing quality information and safeguarding democracy, and how such media needs to adapt to meet future challenges.

As one of the speakers, Ulla Autendrieth will present initial results from the inter-university “Public service: audience acceptance and future opportunitiesExternal link” project, which aims to gather data and trends about youth perceptions of the SBC.

swissinfo.ch will offer live-streaming access to the conference on March 4. The programme and registration can be found hereExternal link.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.