Syria: what will it take to make peace?

It’s a cold December afternoon and I am hanging around outside Door 15 at the Palais des Nations. My colleagues are there too, and we are starting to shiver.

But we are used to it: this is the cold hard slog of covering the Syria talks. Lots of waiting, with very little outcome. The Syrians themselves could say the same thing, only, I would hope, more loudly, and more angrily.

After a while, the Syrian opposition team sweeps in; a few nods to the cameras, a couple of shouted questions, a couple of bland answers about being united, and then they are gone. Not to negotiate face to face with the Syrian government team, of course not, that has never happened in all the years of this appalling war. No, they are off to talk to the UN’s long suffering special envoy, Staffan de MisturaExternal link.

Once again, the process seems headed for the rocks. The Syrian government is not even here. Emboldened by the ground they have retaken, with Russia’s support, President Assad’s team arrived in Geneva a day late, stayed a day and a half, and then left again, to “consult and refresh” said Mr de Mistura, adopting his most urbane diplomatic language.

For days, not even UN diplomats knew whether they would come back. It is not the first time we have witnessed this sort of brinkmanship, in fact it has characterised the Syria talks from the start. In the last hours we have heard that, after Russian pressure, the Syrian government team will come back, but whether they will contribute anything meaningful to the negotiations is far from certain.

Waiting games

Not so long ago we were waiting for the opposition, who huddled in Istanbul or Riyadh, arguing about who was actually the ‘real’ opposition before grudgingly arriving in Geneva, often weeks after the date on which the talks had originally been planned.

We have waited for hours in the sleet outside Geneva’s top hotels, security denying us even the chance to warm our feet, hoping for some information. We have waited in the Palais des Nation’s famous room 3 until midnight, for Staffan de Mistura to brief us.

With so little progress to report on, we have resorted to colour pieces about the rooms (‘just metres apart’ we are told) in which the respective sides meet, and between which Mr de Mistura and his aides shuttle, year after year.

Glacial diplomacy

If our patience is wearing thin, try to imagine what it must be like for Syrian families. Covering these peace talks, I often think about a young Syrian man I met in Zaatari camp in Jordan, in September 2014.

He had already been there ten months, with his wife and two year old child. Another child was due within weeks. He was friendly, he tried to be optimistic, and, more than three years later, he is probably still in his tent in Zaatari. I wonder how he rates his chances of returning home.

And while Geneva’s glacial diplomacy is irritating for us, for those Syrians who remain inside their country, it can be life or death.

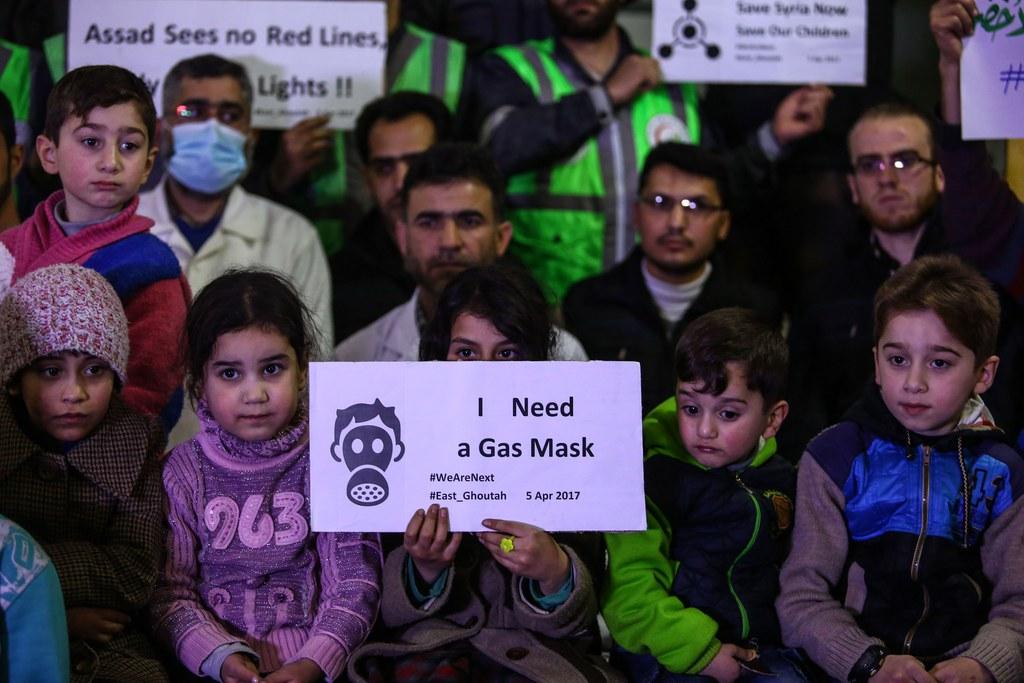

Since May, Jan Egeland, the chair of the UN’s humanitarian taskforce on Syria, has been asking for an evacuation of seriously ill or injured people from the government besieged enclave of Eastern Ghouta. He has a list of almost 500 names, over 100 are children.

Two died last week, nine the week before. Eastern Ghouta is half an hour’s drive from Damascus’ hospitals. This week Egeland, visibly angry, told us about some of those who still cling to life: “Muhammad is 45 days old and has kidney failure. Enji, she is seven years old and she has haemophilia, severe haemophilia. Nour is two years old and she has a rare cancer called retinoblastoma, very rare and very dangerous.”

They have caused no harm in their lives, he said, but men in uniform are blocking the UN ambulances waiting to take them to safety.

Why can’t these men make peace? How many more children who have known nothing but war in their short lives will have to die?

Pessimism

Sadly, ask any of Geneva’s many specialists in conflict resolution, and no one seems optimistic. “No party is willing to negotiate in good faith,” is the verdict of Elodie ConvergneExternal link, a fellow at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy and an adviser on peace processes and mediation in armed conflict.

Civil wars, she points out, are the hardest to resolve, and to do so it is often necessary to arrive at a “mutually hurting stalemate”. That point has not arrived in Syria, or not for the warring parties. Everyone else may be hurting, but the fight goes on.

“Compromise always comes when the cost of not compromising is higher than compromise,” points out International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) president Peter MaurerExternal link. “At the moment, while I hope, I can’t see it yet,”

More

ICRC president warns over ‘explosive mix’ of urban conflicts

“[Between] many of the parties on the ground,” adds Egeland, “the bitterness is so extreme, the hatred really, after seven years of war, is beyond belief.”

But in that bitterness, that unwillingness to compromise, and that desire to win on the battlefield, the lives of children have become bargaining chips. Their right to medical care is put on hold while bartering goes on over what the men who could let the ambulances through might get in return.

Every movement of aid in Syria, every truck load of food, every box of medicine, has some sort of price attached. But, as this war enters its eighth year, the highest price of all is being paid by Syria’s civilians

“The end battles are too bloody, it is coming at an intolerable price,” says Egeland. “Aleppo, may be quiet today, but it came at an intolerable price.”

“Maintaining or gaining influence, territory, or control should not come at the cost of civilian losses,” adds the ICRC’s Maurer.

Staffan de Mistura has said this round of peace talks (the eighth) will last until December 15. The ‘don’t quote me’ view from diplomats is that an agreement to have another round in a few weeks or months would be a positive sign.

Meanwhile, there is still no word on the evacuation of the children from Eastern Ghouta.

You can follow Imogen Foulkes on twitter at @imogenfoulkes, and send her questions and suggestions for UN topics.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.