Aid money: spending every penny wisely

The news that the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) had uncovered fraud in its Ebola operation in West Africa caused surprise and dismay.

The statement External linkwas released curiously discreetly on the IFRC’s website on October 20. To find it, readers had to click on ‘Who We Are’, then click on ‘The IFRC’, then click on ‘Performance and Accountability’, then click on ‘Internal Audit and Investigations’, and there, finally, in fine print on the left, click on ‘IFRC Statement on Fraud in Ebola Operations’.

A cynic might suspect the Red Cross was hoping no one would ever notice the statement, but more generous-minded observers note that as soon as the story did leak out, Red Cross officials, including the Secretary General Elhadj As Sy, made themselves available to the media.

He told journalists the Red Cross was sad and angry at the losses, which could come to CHF6 million ($6 million) or even more, across the three countries worst affected by Ebola: Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.

In the eyes of donors: member states, businesses, and private individuals, these losses could be very damaging. The Red Cross is one of the most trusted aid agencies on the planet. Wherever disaster strikes, be it flood, famine or disease, the first responders, volunteers from national Red Cross and Red Crescent societies, are there to help.

From heroes to villains?

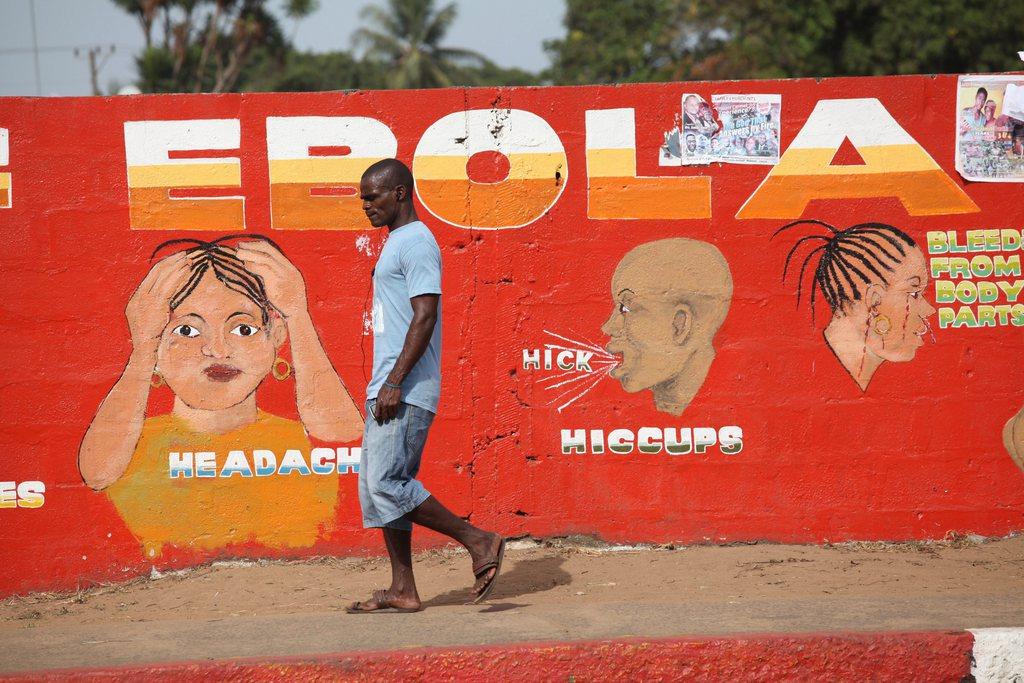

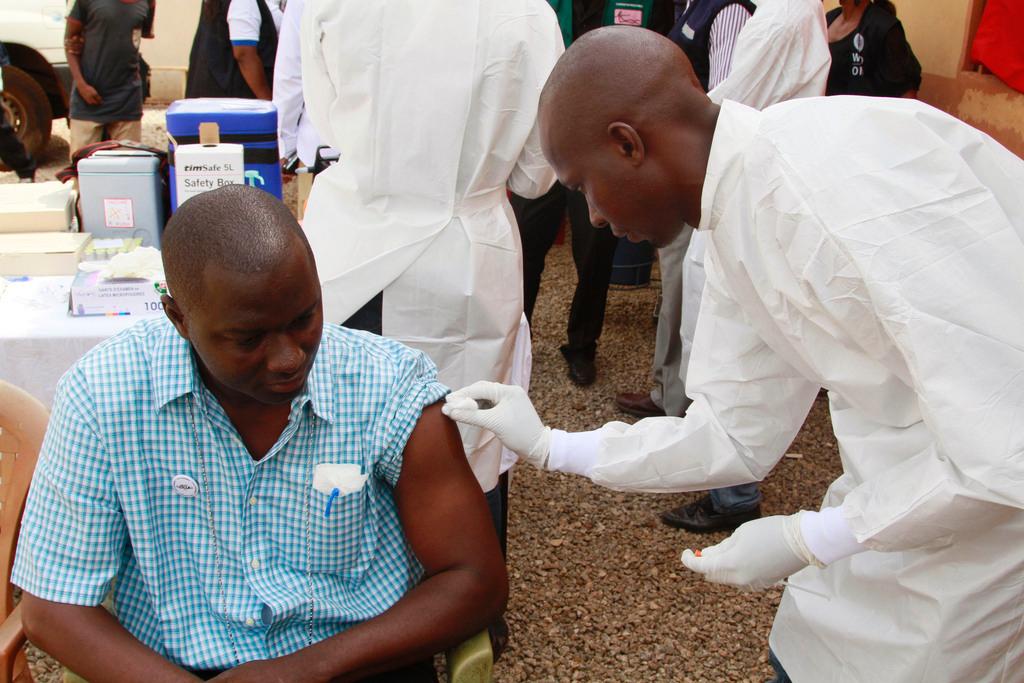

During the Ebola crisis, ordinary Red Cross volunteers were credited with heroic efforts, risking their own lives to save others during an epidemic of a disease which few survive. It was all the more disappointing then, that some members of the national societies in Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone were apparently siphoning off donors’ money for personal gain.

But before jumping to the conclusion that a donation to the Red Cross is money wasted, it is worth reflecting on the complexities of carrying out humanitarian work in conflict and disaster zones.

Aid agencies work, almost without fail, in the poorest, most deprived, and most hazardous places on the planet. Very often, as with Asia’s 2004 tsunami or the 2010 Haitian earthquake, the infrastructure, including the banks, is in ruins. Cash is the only currency. What’s more, aid agencies always try to buy locally (especially when it comes to food) so that the domestic economy is not undermined by a massive foreign aid effort.

This is a combination of circumstances which, like it or not, provide the opportunity for fraud and corruption, whether it is overcharging for foodstuffs, skimming off a few aid dollars here and there for personal gain, or adding false names to lists of beneficiaries to get more for your own friends and family.

In response to the Ebola losses, the IFRC has announced stricter measures to try to combat fraud, including ‘new checking and enforcement measures at each line of fraud prevention defence, cash spending limits in high-risk settings, early deployment of trained auditors as part of the first wave of emergency operations set up, mandatory fraud prevention training for staff being deployed, the creation of an Audit and Risk Commission of the IFRC Governing Board, and the establishment of a dedicated and independent internal investigation function.’

Long history

These measures may help, but no one in the humanitarian community thinks fraud can be eliminated. “Is the risk zero in managing this kind of operation?” asked Elhadj As Sy. “Probably not, but we will do everything… to make sure.”

Aid officials know from bitter experience that losing donors’ money has a long history. In Somalia, at one point, it was estimated that a staggering 50% of all food aid was stolen, some of it by pirates who hijacked entire aid ships, some at gunpoint as food convoys attempted to reach starving communities, and some by petty pilfering.

Then there was the notorious example of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and MalariaExternal link. In 2011 the Fund’s own auditors discovered that in some operations, up to two-thirds of aid money was being misspent. Lurid details of prescription drugs being sold on the black market, of donations being invested not in approved projects but in cars or motorcycles, shocked donors. Some countries, among them Sweden and Germany, put donations on hold until the Fund cleaned up its operation.

Suspension of grants is every aid agency’s nightmare. It means programmes must be reduced, or even stopped altogether. So, given the admitted difficulties of managing aid money in disaster zones, what more can be done to reassure donors?

Total transparency

Judith Greenwood, who is Executive Director of the CHS AllianceExternal link, believes complete transparency is key. “It’s very important that when this (fraud) actually happens, we need to be transparent about it, and absolutely ensure that action is taken.”

CHS stands for Core Humanitarian Standards. The Alliance is an umbrella network for aid agencies who have united around a set of nine common standards and principles to improve humanitarian work. The IFRC is a member.

Greenwood believes the IFRC’s statement about the fraud, the actions it has taken so far, and the promise to hold those responsible to account, are good signs. Ironically, the fact that aid agencies are coming clean about financial impropriety might lead some to think misspending is happening more often, when in fact the opposite is more likely to be the case.

And there is another problem: stepping up fraud prevention measures costs money, and that spend will almost certainly appear in an aid agency’s ‘administration’ budget, opening the door for critics who claim humanitarian organisations are top heavy on bureaucracy.

That is why Greenwood believes accountability and transparency must apply not just to donors, but to recipients. Everyone needs to know that money for an aid project is not only being well spent, but that the project itself is beneficial.

“Accountability is also to the people and communities who are affected by crisis. And I think that combination of the two will help to reassure,” she said.

But she also agrees, however hard aid agencies try, eliminating the risk of corruption altogether may be impossible.

“Practically speaking, adopting our common standards I think helps to minimise [that risk], we’d like to say prevent, but I don’t think that that is realistic,” said Greenwood.

You can follow Imogen Foulkes on twitter at @imogenfoulkes, and send her questions and suggestions for UN topics.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.