How a Swiss scientist saved 20 million people

Insect expert Hans Rudolf Herren’s work in tackling the devastating cassava mealybug crop pest in Africa saved millions of lives and won him the 1995 World Food Prize.

Herren, the subject of a new biography, tells swissinfo.ch how he managed to naturally control the bug using a method that involved shooting the insect’s natural enemy, a type of wasp, from aeroplanes across huge swathes of Africa.

The scientist was only 31 when he took a job in the middle of a crisis: the mealybug was decimating Africa’s staple crop, cassava. After ten years, his radical, non-chemical solution had turned the situation around and averted a famine. He is so far the only Swiss to receive the World Food Prize.

Herren has since continued his research into insects and natural pest control in plants, animals and humans.

In 1998 he set up the Zurich-based Biovision foundation with friends, using money from his various prizes, to promote sustainable organic agriculture in Africa. He is also president of the non-profit Millennium Institute in Washington, which promotes sustainable development.

swissinfo.ch: The biography’s title is: How Hans Rudolf Herren saved 20 million people. How did you do this?

Hans Rudolf Herren: We knew that the mealybug was not of African origin. That’s actually one of the reasons it spread like wildfire after its introduction because it had no natural enemies. Specialists decided it was a species from the New World and also from somewhere where cassava or any of its wild relatives would occur.

Cassava comes from the Amazon region so it was quite clear that somebody must have transported cuttings or plant material to Africa and brought the pest in. So the plan was to find where this mealybug had come from, check if there was anything useful you could connect to it and then bring this information back to Africa.

swissinfo.ch: So it was a lot of detective work.

H.R.H.: It was. What was interesting was that in all the many years scientists had studied cassava in Latin America, no one had seen the mealybug.

This seemed very strange to me. I thought it may actually be on one of the wild relatives of the crop. Eventually it was found in the border area of Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia, interestingly on cultivated cassava.

But no one had seen it there because it was a very low population. In the Americas there are very few mealybugs which meant something was keeping it under control.

swissinfo.ch: You found out that it was a type of wasp.

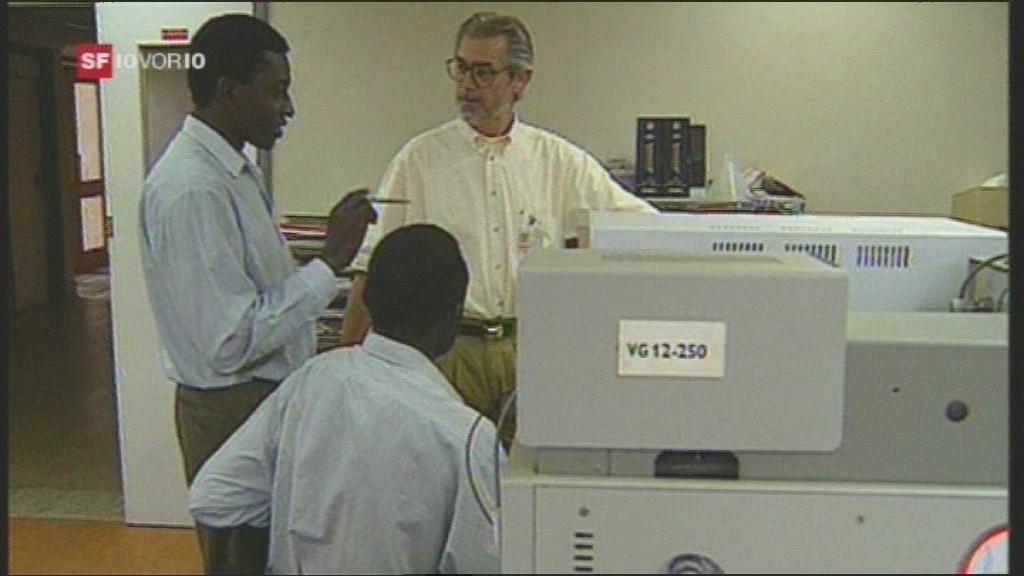

H.R.H.: Yes, it was a parasitoid wasp [which lays eggs into the bug, eventually killing it]. We had a big factory to produce hundreds and thousands of them and they were packaged in a way that they could be shot out of an airplane travelling at 300 kilometres per hour or more across Africa, from Senegal on one side to Mozambique on the other.

We were careful that it was specific to the cassava mealybug. Thirty years later, no problem has been created and the mealybug is still under control.

swissinfo.ch: Agriculture today still involves the use of many chemicals and even genetic technology. How does your vision of using nature’s tools fit in?

H.R.H.: The International Assessment of Agricultural Science and Technology for Development IAASTD report [published in 2008], of which I was co-chair, made clear that we needed a radical change to agriculture for both developed and developing countries.

The authors decided that we needed to change from this industrial, energy intensive agriculture and from the very traditional agriculture that has a low input and productivity towards a multifunctional, agro-ecological, organic type of agriculture which is self-regenerating.

Biovision was almost ahead of that report by promoting an ecologically-based agriculture, which is in harmony with the system, which doesn’t fight the environment but works with it, and which will produce enough to nourish everybody by 2050. I’m convinced we can do it. The question is can we actually implement it now?

swissinfo.ch: The book describes you as “restless bird” flying around the world in great demand for your expertise. Any plans to slow down?

H.R.H.: No slowing down because there is still so much to do still. My main job is now with the Millennium Institute where we are trying to change policies.

We need to think now long-term and in systems because when you look out there everything is connected: whatever you do in one part of the world will affect somebody in another part, eating habits will influence how farmers grow food, how much pesticides they use, because you as a consumer can decide what kind of a world you want. The consumer decides everything.

The main policy issue is whether governments are ready to tell consumers to pay the true cost of food, including all external costs which are produced by industrial agriculture, such as water pollution, loss of biodiversity and social and health problems.

These are all costs society is paying now. We say they have to be included in the product’s price so people have a choice. They can buy fair trade, organic, multifunctional products, or they can continue to buy from industrial agriculture. That would be one way of changing how we do agriculture. But these kind of policies are not very easy to implement. It’s not very popular to increase the price of food, but it will have to happen.

Herren was born on November 30, 1947 in canton Valais. He grew up on a tobacco plantation, which was intensively farmed. As a boy, he helped spray chemicals.

After training to be a farmer, Herren studied at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, gaining a PhD. He then completed post-doctoral research in ecology at Berkeley.

He worked in Africa for 27 years, at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) in Nigeria (mealybug project, among others) and as director of the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE) in Nairobi, Kenya.

In 2005 Herren was appointed president of the Millennium Institute in the US. He has an organic vineyard in California and is married with three grown-up children.

The biography, by Herbert Cerutti, was published in May under the title: How Hans Rudolf Herren saved 20 million people: a Swiss man’s ecological success story.

Founded in 1998, Zurich-based Biovision is a non-profit and independent Swiss foundation. It tackles problems such as infection diseases, animal epidemics, crop pests and over-exploited ecosystems, which all contribute to cripple development in East Africa.

Biovision uses sustainable, scientifically-founded methods and works closely with local partners and people living in the area. It argues that most people in Africa are small-scale farmers whose existence is dependent on the quality of their natural resources and thus need an intact environment, fertile soil, good harvests and healthy livestock for their welfare and that of their communities.

For example, there is a project to encourage beekeeping in Ethiopia, as bees are important for agriculture as they pollinate plants. Locals are being shown how they can protect themselves from malaria by using simple methods and avoiding chemicals. Biovision also publishes the Organic Farmer magazine to transmit knowledge to local farmers.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.