Facing up to Switzerland’s Roman past

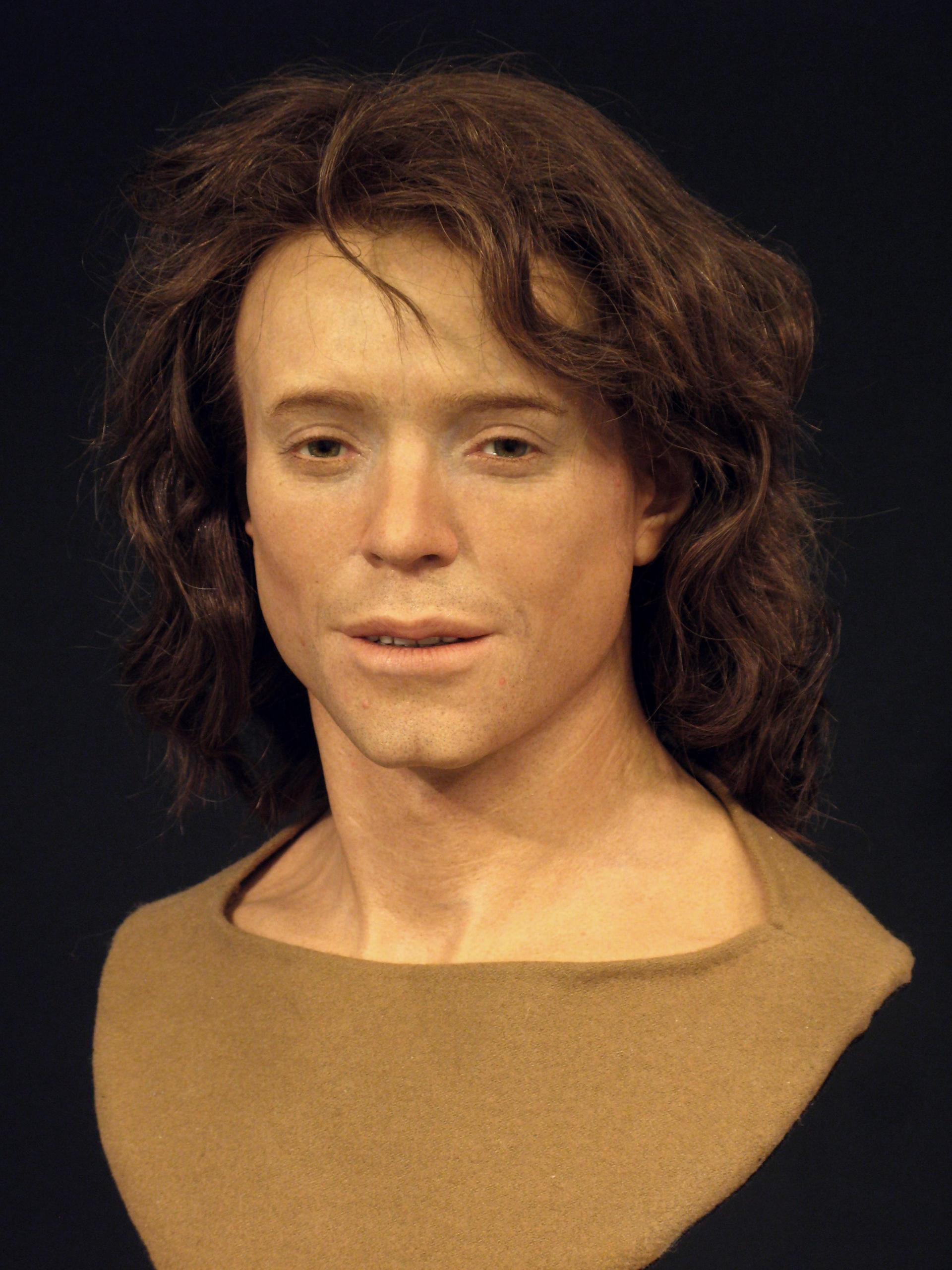

Meet Adelasius Ebalchus. He lived in what is now northern Switzerland some 1,300 years ago, centuries after the collapse of the Roman Empire. Who was he and what can he tell us about life during the Early Middle Ages?

“Adelasius was a young man, about 20 years old, who lived around AD700,” explains Angela Kummer, director of Grenchen Cultural-Historical MuseumExternal link, where his bones and a reconstruction of his face are on display until June 9.

“He was a descendant of the Gallo-Roman population who lived in the region when the Germanic tribes came into the central Swiss plateau in the 7th century. We know very little about this epoch. There are no written sources – people didn’t write anything down – so we have to read what we can from the cemeteries, the skeletons and the remains in the burial sites.”

His intact grave, lined and covered with stones, was in fact one of 47 that were excavated in 2014 in the town of Grenchen, canton Solothurn.

“Because he was buried in an expensive, walled grave, he probably belonged to the richer classes,” Kummer says. “He’s also got an excellent set of teeth! Back then people very often ate hard grains – gruel was a staple food – but their milling wasn’t that good, so it was quite gritty and ruined many people’s back teeth. Adelasius’s teeth are very healthy – no plaque or rotting or missing teeth – and they are nicely positioned, although they are also slightly worn down by the grains.”

What’s more, he was 173cm (5’7”) – relatively tall for the time, Kummer says. “That’s another clue that he had a good childhood, with enough food for his development. It’s exciting what you can see just from the bones!”

Facial reconstruction

That said, he still died aged around 20, at a time when life expectancy was 30-40. But he probably didn’t come to a violent end; rather a chronic infection, perhaps triggered by a lung inflammation, might have finished him off, Kummer says.

“Various traces of infection were found in his bones, the disease lasted for a long time and led to deficiency symptoms. But he probably died from [one of those explanations] and not in a battle or anything like that.”

Around 1,300 years later, Swedish archaeological facial reconstructor Oscar NilssonExternal link was commissioned to rebuild Adelasius’s face.

“Many people think he must almost be Neanderthal and they think of someone with a beard and long hair and who’s unkempt,” Kummer says. “Oscar Nilsson ‘shaved’ him, so you can see his cheekbones and the cleft in his chin – and you can see that when you look at his skull. He wouldn’t stand out walking down the street today! Although beards are now back in!”

Pleasant surprise

Mirjam Wullschleger is leader of the project and a member of the cantonal archaeology teamExternal link that gave Adelasius his distinctly Latin name.

She says that at a time when Germanic tribes, the Alemanni, were slowly entering the central Swiss plateau, Adelasius was “a local, a Roman”.

“The graves here in Grenchen are typical for the area of the Romans, the old, settled population that lived here,” she says, explaining that during the time of the Romans no Romans actually came to the region around Grenchen – the inhabitants were in fact an indigenous Celtic people who had taken on the Roman way of life.

“Adelasius most probably spoke a development of the Latin dialect that was spoken here at the time of the Romans.”

Wullschleger admits she was surprised by the quantity and quality of the graves found in the former medieval cemetery that has since been covered by a block of flats.

“We knew graves were buried there because in the 19th century local historians went there looking for these graves – and they found at least 90 – but in 2014 we didn’t know how many were in this field. I thought almost all the graves had already been excavated, but we were positively surprised when we found many well-preserved, intact graves.”

So why is Grenchen such a hot spot for early medieval skeletons? “I think above all it’s due to the location – the southern foot of the Jura mountains lies on an important traffic axis. Also the soil here is very fertile. These south-facing raised terraces have always been of interest to people. So we simply find these remains where people lived.”

Adelasius’s remains and the reconstruction of his face will go on permanent display in the autumn in the new House of MuseumsExternal link in nearby Olten.

“It’s very important that what we find during the excavations doesn’t disappear into our cellars or archives but is displayed to the public,” Wullschleger says.

More

Unwrapping the medical messages of mummies

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.