Southern Europe tries to escape political chaos

Citizens living in the Mediterranean region of Europe and their political freedoms have suffered repeated setbacks over the course of history. But despite crisis and chaos at a national level, local initiatives give new hope.

The latest stops of the #ddworldtour are Lisbon, San Sebastián and Rome.

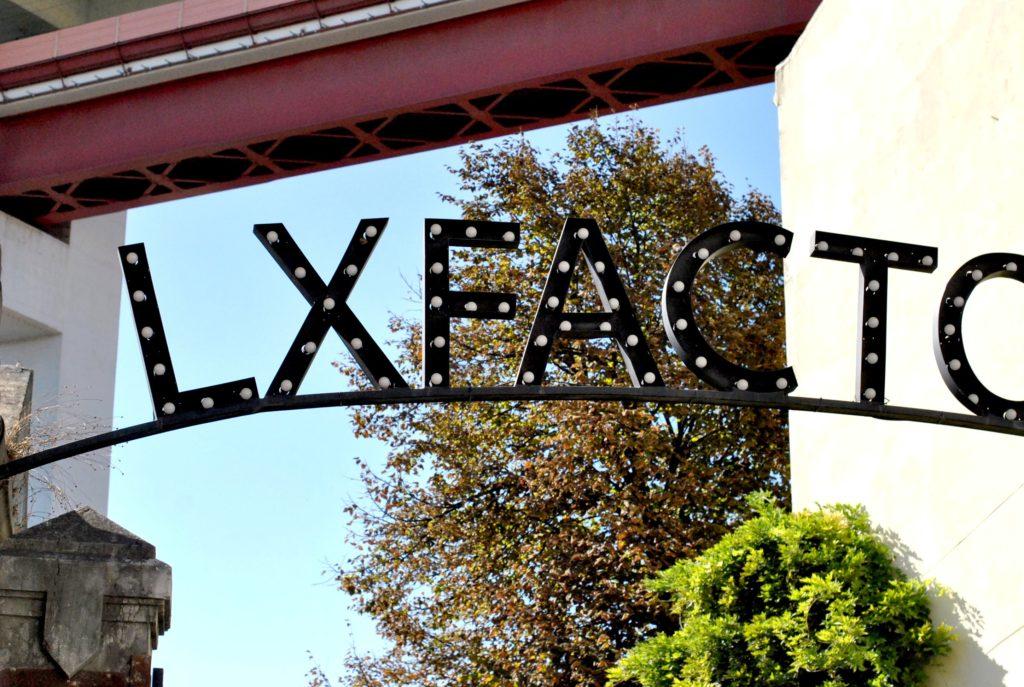

This is magical place. A jumble of small restaurants, start-up companies, theatres, big halls, and people from all walks of life and corners of the world.

This is LX FactoryExternal link or – in the local language – “Companhia de Fiacao e Tecidos Lisbonense”. Established back in 1846, when Portugal was a major global power, this hip neighbourhood symbolises the ups and downs of Lisbon, the national capital.

“We are very proud of our history, country and city,” says Lourenco Jardim de Oliveira, a young consultant working for the city of Lisbon on participatory and direct democracy: “But many things are not as good as they look.”

However, my most recent visit gave me fascinating and encouraging insights into a city which – after decades of authoritarian rule, mismanagement, corruption and youth brain-drain – has become one of Europe’s true hotspots.

In the shadow of the gigantic suspension span called the “Bridge of 25 April” (after the successful revolution against the military rulers in 1976), the LX Factory, reopened after a process of participatory budgeting, underlining the novel approach.

“We need to rebuild trust between citizens and public institutions,” says Graca Fonseca, the minister for modernisation. The Socialist leads the ten-year-old efforts to convince the Portuguese citizens of participatory budgeting — an idea originally inspired by similar initiatives in the southern Brazilian town of Porto Alegre.

Recent political changes in Brazil showed the weaknesses of the scheme, which was dependent on the goodwill of those in power. But Lisbon and Portugal has shown more patience in establishing, strengthening and developing participatory budgetingExternal link, now covering about 5% of the city’s and the country’s annual budgets.

Unlucky referendum history

In a way, it is a form of introducing the financial referendum process, widely used across the United States and Switzerland, through the backdoor.

It gives the citizens a direct say in how their tax money is used to serve the public. There are differences, of course. While financial referendum procedures empower citizens directly at the ballot box, participatory budgeting procedures focus on deliberative methodology.

For Jardim de Oliveira, the practices applied in Portugal are not sufficient yet to change the deeply rooted paternalistic mentalities in his country.

“Ultimately many elected officials are not really responsive to their voters at all,” he says. This lack of responsiveness reflects very weak direct democratic features in modern Portuguese history.

In fact, the only two nationwide popular votes on substantive matters took place on June 28, 1998. They were initiated by the Socialist government as non-binding plebiscites and dealt with abortion and regionalisation. Many voters abstained and the instrument of the ‘referendum’ was discredited.

Economic and political crisis

Beginning in 2008, a deep economic and political crisis forced many Portuguese to leave their country. Only recently have Lisbon and Portugal experienced an economic upswing, combined with political stability.

“Now, we are ready for the next step in making this wonderful city and country a much more democratic place,” says Jardim de Oliveira before I board the last international night-train on the Iberian peninsula. The “Sud Expres,” links Lisbon with Donostia-San Sebastián at the French-Spanish border.

San Sebastián has a long history of sailors and fishermen leaving home for months to discover the world and becoming rich.

In this beautiful city on the Atlantic coast I met Urtzi Arriaga. He leads a small company “Simplecomunicacion” (simple communication) and participated in last year’s Global Forum on Modern Direct DemocracyExternal link here.

Twelve months ago, Europe’s 2016 culture capital hosted this travelling global networking event of civil society activists, scholars, politicians, election administrators, journalists and business people (for full disclosure: the author of the #ddworldtour notebook is deeply involved in this).

The four-day exchange on political culture and direct democracy encouraged Arriaga and the regional government of Gipuzkoa to launch a comprehensive democratic strategy programme.

“We want to make our region one of the most democratic in the whole of Europe,” he says.

Arriaga points to the experiences of Donostia-San Sebastián where the challenges are somewhat different from those in Lisbon and Portugal.

It is not an outdated Portuguese political mentality but rather an inflexible system of the Spanish state, which makes the democratic life of the Basque Country, to which San Sebastián and Gipuzkoa belong, so difficult.

After years of terrorism, the Basque Country now is a peaceful and wealthy place. “But we are still very much limited in our autonomy,” says Arriaga. He refers to Catalonia, the nearby region in northeastern Spain and its recent political developments.

An illegal October 1 referendum on independence that led the Spanish government to take control over the prosperous region with 7.5 million residents and to initiate new elections to take place on December 21 this year.

Beautiful and functioning poorly

Elections are also due in Italy – the third country I visited on the latest leg of my #ddworldtour.

The notorious political instability is a dominant feature in one of the heavyweights of the European Union with a population of more than 50 million. It has had 65 different national governments since becoming a republic by popular vote back in 1946.

Swiss-Swedish author and journalist Bruno Kaufmann has set off on a world tour to explore the state of democracy visiting more than 20 countries on 4 continents until May 2018.

swissinfo.ch publishes a weekly Notebook and multimedia reports by Kaufmann over the next few months as part of its coverage of direct democracy issues.

Kaufmann’s democracy world tour is mainly sponsored by the Swiss Democracy FoundationExternal link, where he is the director of international cooperation. The Swiss Democracy Foundation hosts various projects and platforms linked to participatory and direct democracy across the globe, including Democracy InternationalExternal link, the Direct Democracy NavigatorExternal link and the Initiative and Referendum Institute EuropeExternal link.

But Italy is also a deeply democratic country with strong social movements. At the same time it is the victim of non-state networks (mafia, families, underground sects) and over-institutionalised governments with a multitude of power centres and overlapping jurisdictions.

“Harmonised chaos” as Giancarlo Giorgetti described it in a public hearing in parliament this week.

In other words: Italy is beautiful and elegant, but it functions surprisingly badly. And what’s true for Italy as a whole is even more true for its historic, political and cultural heart: the capital, Rome.

The four-million city at the Tevere river has seen mayors coming and going for a long time. The most recent example is Virgina Raggi, a 39-year-old lawyer, who was elected in summer 2016.

A political outsider, Raggi first was politicised when she became a mother a few years ago and discovered the insufficient public infrastructure of Rome.

While somewhat despairing at the ungovernability of Rome, Italy and her own political party (the Movimento5Stelle) Raggi has initiated a local constitutional reform at the city level. By September next year, when the 2018 Global Forum on Modern Direct Democracy will take place at Campidoglio, City Hall, Rome shall have a much more participatory basic law.

“We also want to become part of a global network of democracy cities,” says Angelo Sturni, the leading light in drafting the new constitution.

The discussions with Raggi, Sturni and many others in Rome concluded my brief #ddworltour across southern Europe this week. But the struggle for more democracy in the Mediterranean region – the cradle of democracy – is not over. It remains to be seen if these engaged locals will be able to pull their cities out of their notorious political muddle.

#ddworldtour Notebook

Follow the tour on #ddworldtour @kaufmannbruno @democracyreporter and /people2power.info

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.