Dictator assets law could be short-lived

Switzerland has attracted praise for a new law on returning illicit dictator funds, but doubters say it won’t be useful for long.

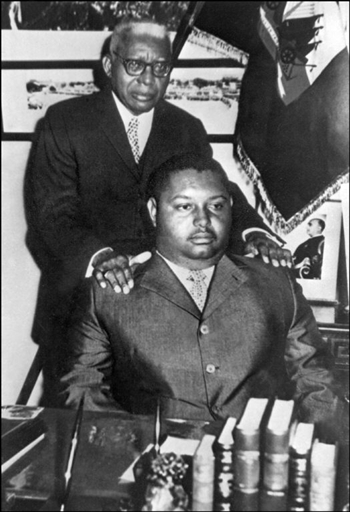

The law comes into force on February 1, and although applicable to assets stashed away by all autocrats, it was tailor-made to deal with the ongoing freeze of assets deposited in Switzerland by former Haitian dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier.

After it was announced in September, Mark Vlasic, the international legal advisor to a team acting to recover Charles Taylor’s assets for Liberia, wrote an opinion piece in the New York Times in which he said Switzerland was “poised to become an example of one of the most forward-leaning countries in the quest to return stolen assets to developing countries”.

“Let us hope that other major financial centres follow suit,” he wrote.

Under the new law the Swiss cabinet can block contentious assets and will have up to ten years to launch action to confiscate the assets once they have been blocked. Once returned to their country of origin, the funds must be used to improve quality of life for the wider population, strengthen the judicial system and fight against crime.

Duvalier funds

Duvalier’s assets have been frozen in Switzerland since 1986, shortly after he was ousted. The new law should help resolve a situation in which the funds were due to be given back to Haiti but were at risk of falling into Duvalier family hands.

After February 1 the Swiss government will decide whether to take the-then legal step of confiscating the Duvalier assets – totalling around $5.8 million (SFr5.48 million). The sum may seem small when compared with $700 million Switzerland returned to Nigeria from former dictator Sani Abacha in 2005, but giving the Duvalier funds back to Haiti will be seen by many as a moral victory for the country.

Duvalier has contested Switzerland’s freeze of the assets and his surprise return to Haiti on January 16 prompted some observers to say this was an attempt to lay claim on the funds.

For his part, if Duvalier wants the funds unblocked, Swiss law states that he will have to prove that the assets were earned legitimately, something few believe he can do. If he cannot, they will be returned to Haiti.

One-off law

For the Berne Declaration, part of a coalition of non-governmental organisations campaigning for the return of Duvalier funds to Haiti, the law will be a step forward for the Haitian scenario but will not be helpful in other cases.

“The foreign ministry is being described as a champion of a law that will enable us to have a clean financial centre. We say that’s propaganda. The reality is that this law will be useful for the Duvalier case but never again,” the organisation’s financial expert Olivier Longchamp, told swissinfo.ch.

There are flaws in the law’s ability to stop illicit funds arriving in Switzerland, he noted. Current monitoring by banks of suspicious funds has not worked so far, failing to stop assets being deposited in the country by deposed Tunisian President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, for example.

“We think the law goes in the right direction but it’s a very, very small step. It is totally inadequate.”

Global crackdown

Daniel Thelesklaf, executive director of the Swiss-based International Centre for Asset Recovery, believes the Duvalier case will be a test of its effectiveness.

Technically it only applies to so-called “failing states”, he notes. All other countries would have to come up with a conviction against a former dictator – no easy feat for a country in upheaval. And before the law can be enforced, assets have to be frozen – which implies that the said country knows where a dictator has hidden its assets.

This limits its effectiveness as a preventative measure, Thelesklaf says.

There are other potential problems too. While the new law requires the reporting of suspicious transactions, only a fraction of such actions are reported today.

Instead, “international cooperation remains key” if states want to keep out dictator assets, he told swissinfo.ch.

This involves exchanging information of suspicious activity between countries, giving countries early notice when dictators set up accounts abroad and governments employing staff for the sole purpose of following international financial probes.

It’s a view backed by Mark Vlasic in his aforementioned New York Times piece: “It is only by international collective and targeted action that we can ensure that there will be no safe haven for stolen assets,” he wrote.

According to the World Bank’s Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative, a body of which Switzerland is a supporter, a number of important international agreements and commitments to common standards have been made over the past decade.

“The challenge going forward is to translate these commitments into action, preventing the laundering of the proceeds of corruption and making progress in asset recovery by getting investigations underway, securing successful prosecutions and judgments, and returning the proceeds of corruption so that they can be used for development and poverty reduction purposes,” says the initiative.

April 1986: Haitian government asks Switzerland to freeze Duvalier assets in Swiss banks.

June 2002: Swiss cabinet blocks assets for three years.

January 2008: Geneva judge says the 1986 request for legal assistance was inadmissible due to the statute of limitations. But funds remain frozen owing to a government decree.

May 2008: Haiti applies for the case to be reopened and the Swiss Justice Office agrees to provide judicial assistance.

August 2009: The Federal Criminal Court rejects an appeal by the Duvalier family to reclaim the money, saying they failed to prove that the money was of legal origin. It said the family diverted public funds into the Swiss accounts through a Liechtenstein foundation which was tantamount to a “criminal organisation”.

January 2009: The Federal Court turns down a bid from the Federal Justice Office to have the money returned to benefit Haiti.

February 2010: Swiss issue emergency decree to freeze assets until planned law on illicit dictator assets comes into force in 2011.

March 2010: Relatives of Duvalier appeal against Swiss decision. The appeal is still pending with the Federal Administrative Court.

September 2010: Parliament approves asset law.

January 2011: Duvalier returns to Haiti but faces claims for retribution from alleged victims.

February 1, 2011: New dictator assets law comes into force. Swiss government considering launching action to confiscate Duvalier funds.

Marcos, Philippines (1986 – 2003): $684 million returned to country

Abacha, Nigeria (1999-2005): $700 million returned to country

Montesinos, Peru (2002-2006): $92 million returned to country

Salinas, Mexico (1996-2008): $74 million returned to country

Mobutu, Congo (1997-2009): $6.7 million returned to Mobutu’s heirs.

Gbagbo, Ivory Coast: (2011-): n/a

Ben Ali, Tunisia (2011-) : tens of million of dollars

Duvalier, Haiti (1986-2011): $5.7 million still frozen

(With input from Samuel Jaberg)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.