Scientists find novel way to test for toxins

Researchers in Switzerland and the United Kingdom have developed a method for testing the environmental impact of chemicals using isolated cells instead of live fish.

A fish in a stream is like a canary in a coal mine: it is likely to be the first to be affected by toxins in the environment. Their high sensitivity to water contamination makes fish prime candidates for toxicological research, and about one million fish are used in Europe every year to assess the environmental safety of chemicals like pesticides.

Apart from the ethical concerns associated with animal testing (it can cost 400 fish lives to determine the impact of a single chemical on their growth), it is also an expensive and time-consuming process for chemical companies, experts say.

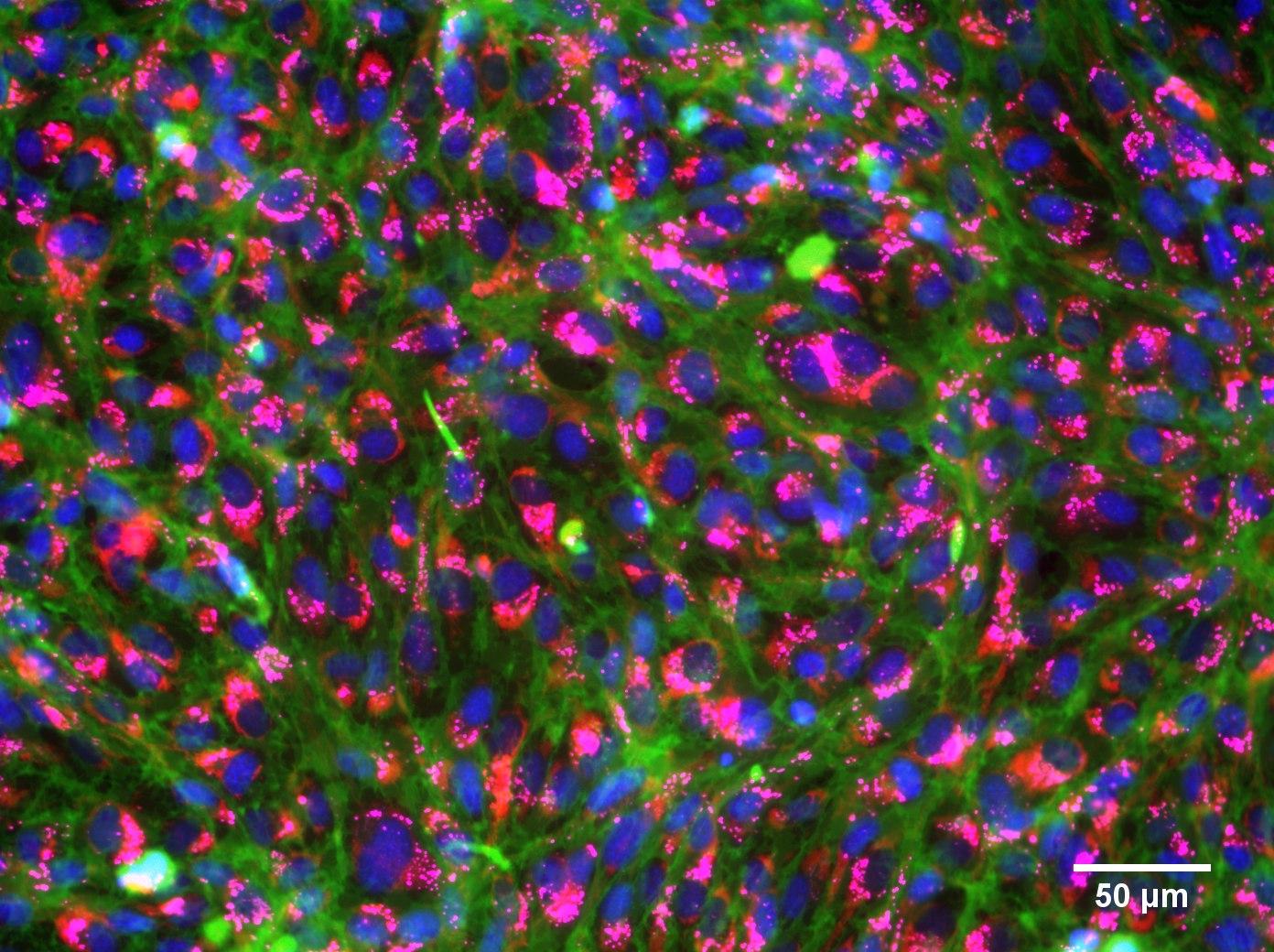

The Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag) External link has worked with the Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology in Zurich and Lausanne and the University of York to develop a faster, kinder solution to the problem: testing chemicals on gill cells in the laboratory.

Depending on how quickly the gill cells have increased in number five days after exposure to the test chemical, researchers can determine the effect of the compound with the aid of computer modelling. Put simply, the more a chemical appears to slow the growth of the cells, the more toxic it likely is.

The results were published on Friday in the journal Science Advances.External link

This is a major step towards simpler, less expensive and more rapid toxicity testing for the authorisation and use of new chemicals,” said Eawag environmental toxicologist Kristin SchirmerExternal link in a statement. “It’s the first time we’ve been able to use cell cultures to accurately predict chemical effects on growth which would only emerge after weeks or even months in live fish.”

The scientists will have to perform further tests to determine whether gill cells can be used to represent the effects of chemicals on the entire fish, or whether different tissues react to the compounds in different ways.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.